Basalt on the Boundary

Join Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Archaeologist Greg Walter as he explores the basalt stone walls of Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland.

Why basalt stone walls?

One of the most common archaeological enquiries received at Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga relates to basalt dry stone walls that some properties have on one or more boundaries.

Many enquirers are surprised to find that walls may be archaeological sites as defined in the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014.

In view of that, we've put together a presentation to give background information on these walls, their origin and location and the implications of dealing with them under current legislation.

These walls are common in areas surrounding Auckland's volcanic cones and in this presentation we have largely focused on the area south of Maungawhau/Mt Eden and the suburb of Balmoral.

Kaitiaki Māori stonefields

Prior to European settlement of the area, the land and its fertile soils around Maungawhau and other volcanic cones had been occupied by Kaitiaki Māori, who practiced their own form of land clearance and use of the basalt resource in their stonefield horticultural systems.

Unfortunately, most stonefield areas in the central isthmus were modified or destroyed by development, and their associated archaeological evidence removed well before archaeological recording became commonplace.

However there is little doubt that this material was repurposed and used by colonial settlers when the land was cleared.

The suburb of Mount Eden

The suburb of Mount Eden was one of the earlier of Auckland's fringe suburbs to be developed, between Dominion, Mount Eden and Sandringham Roads.

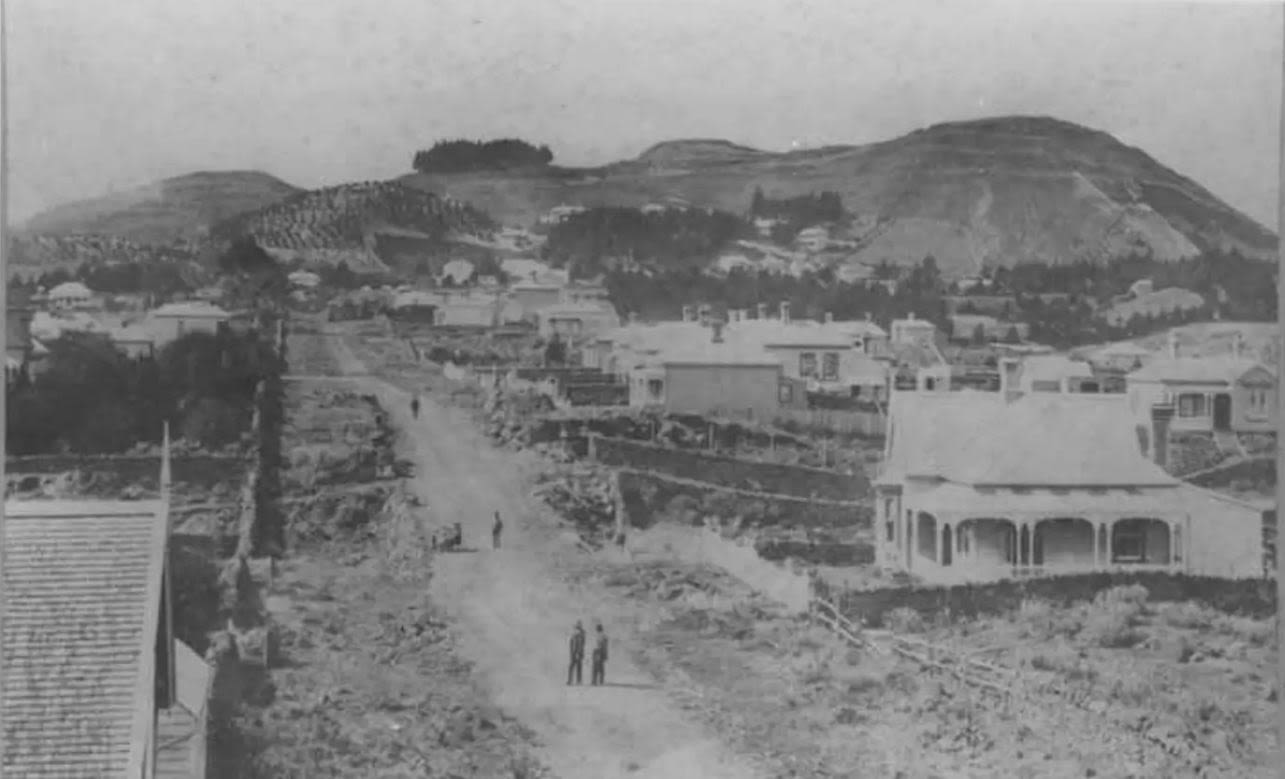

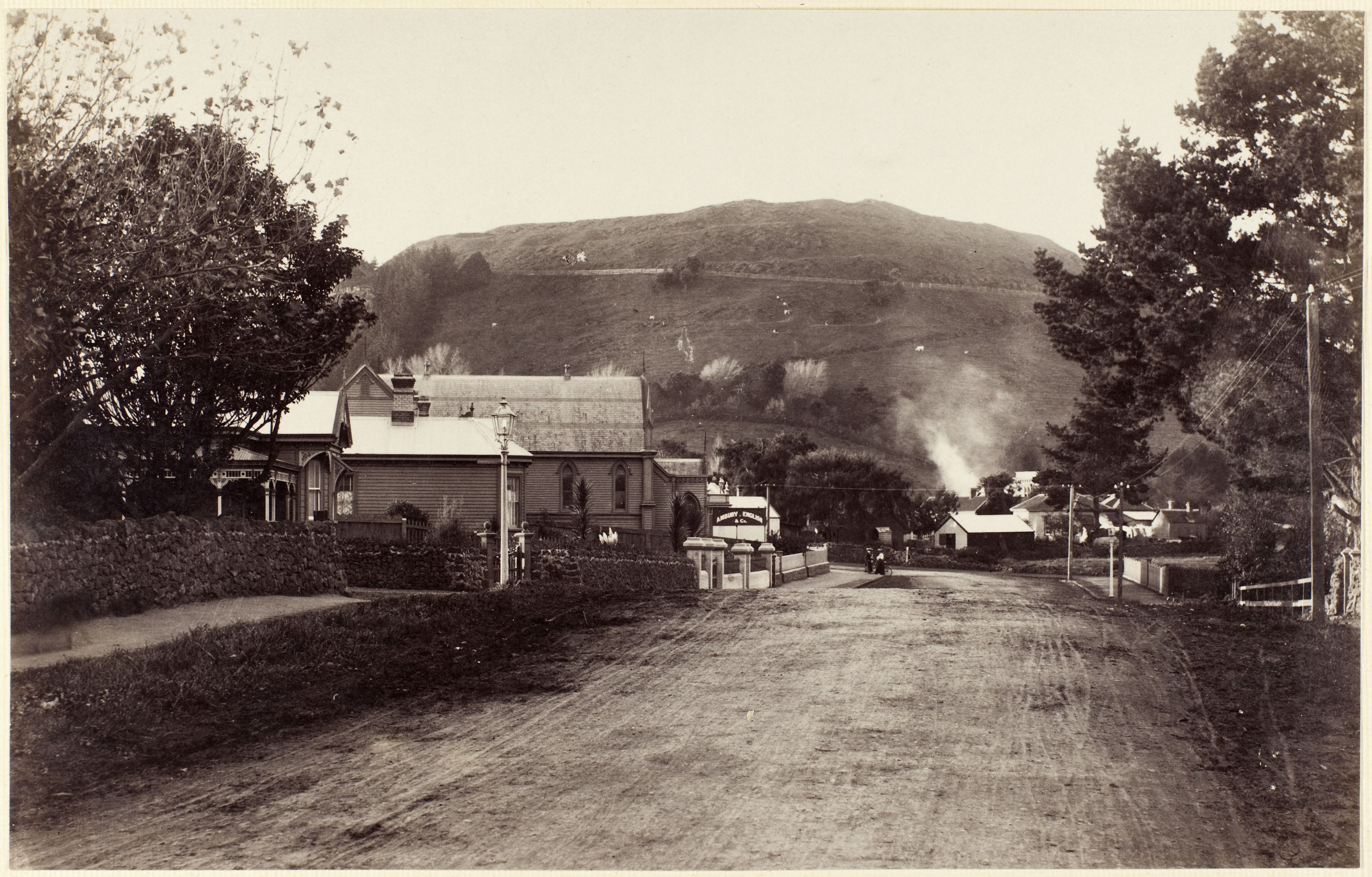

Contrast the contemporary image of View Road (below) to the nineteenth century photo (the black and white image) when View Road was basically a single lane dirt track.

In the 1887 view of View Road, several houses can be seen, a number with basalt dry stone walls on their front or side boundaries.

While this is significantly different to the modern streetscape, it was not the first colonial footprint on the landscape.

The 1841 allotments

Many of the rock walls that currently demark residential sections actually pre-date some of the houses that were built on them in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

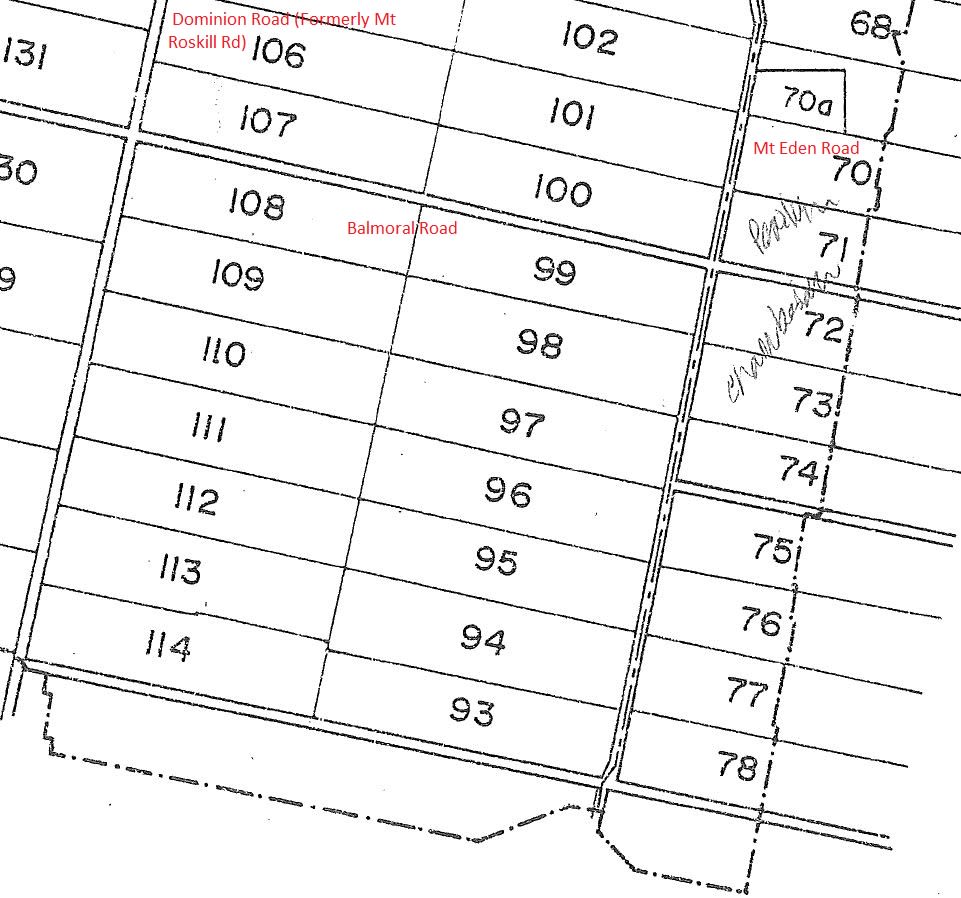

In 1841, the land between Dominion (formerly Mount Roskill) Road and Mount Eden Road was divided up into rectangular 20 acre (approximately eight hectare) allotments intended as small farm holdings.

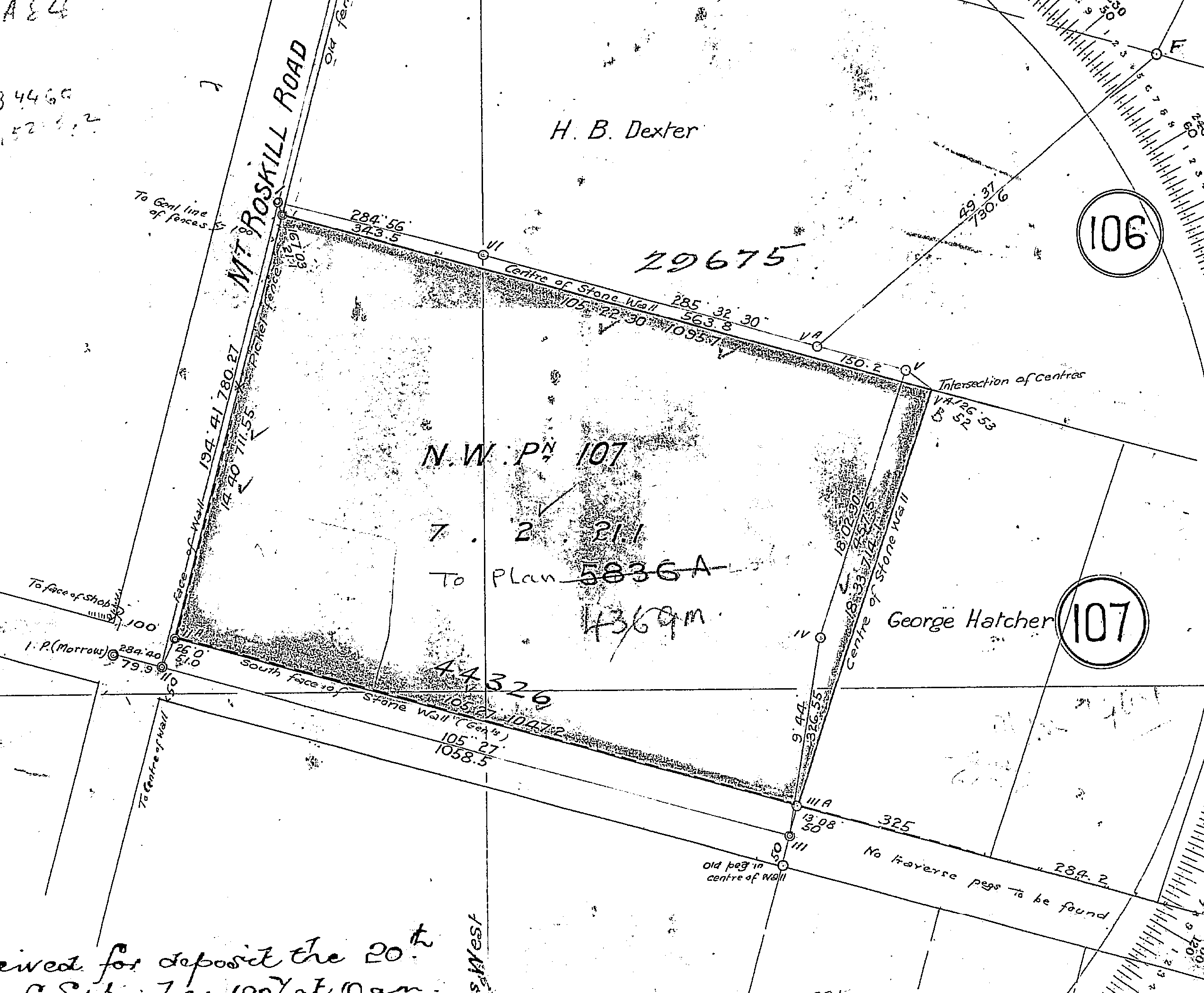

This image shows what is now the suburb of Balmoral, as it was originally subdivided.

Property speculation is not a new phenomenon, the original purchasers of the allotments often turned them over for a quick profit and they could go through a succession of owners before being developed further.

Mt Eden: remnant volcanic landscape

The area around Mount Eden was a remnant volcanic landscape with basalt rocks laying on the surface.

It was common in such landscapes for the rock to be cleared and used to build walls to enclose a property, ensuring animals were confined and indicating the boundary.

This 1940 aerial photograph shows a similar remnant volcanic landscape around Panorama Road, Mount Wellington prior to clearance.

The Balmoral allotments

In Balmoral, many of the eight hectare allotments were walled in this fashion, with the available stone being augmented by quarried material which was also available nearby.

Some sections of these original walls, incorporated into subdivision plans still exist, and have survived various phases of subdivision and development subsequent to their construction.

Identifying allotment boundaries: then and now

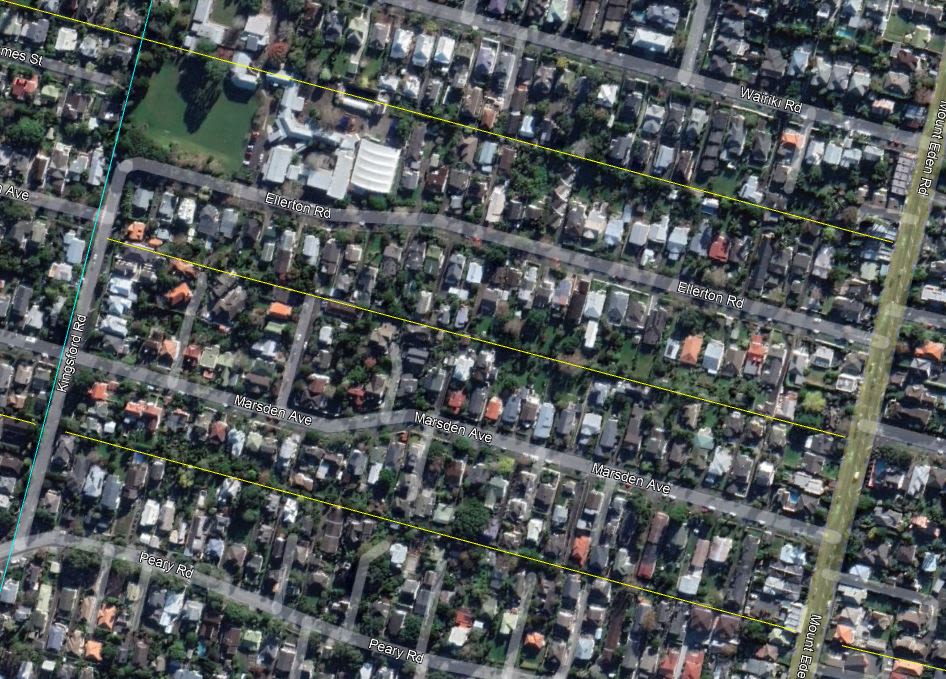

Using a mixture of aerial photos, historic plans and photographs it is often possible to discern the original allotment boundaries through the remnants of the stone walls that once encircled them.

The east-west boundaries of the allotments often ended up being the boundary between two subdivisions, the existing stone walls being left in place.

Some of these are visible in the photographs below, just above the yellow lines. The north-south boundary separating the original allotments still exist in part, although in places streets run down the boundary (shown in teal).

Balmoral allotments 96 and 97 in 1940.

Balmoral allotments 96 and 97 in 1940.

The above aerial photograph of Balmoral dates from 1940. The yellow lines highlight what were originally allotments 96 and 97.

Most of this area was subdivided into residential lots in the late 19th/early 20th centuries. This shows most of the original sections at their full size and before trees had become established, obscuring the boundaries.

Balmoral allotments 96 and 97 in 2023.

Balmoral allotments 96 and 97 in 2023.

Boundaries in 2023

The 2023 view (above) shows that many of these original property boundaries are intact.

It is also to be expected that a certain amount of wall attrition would have occurred over the intervening years as sections were further subdivided, infilled and re-landscaped, resulting in the walls being modified or removed altogether.

Such areas where dry stone walls were prevalent exist throughout Auckland, particularly in areas that are in proximity to one of the 53 volcanic cones and features in the city.

Devonport, Mount Eden, Epsom, Mount Albert, Mount Wellington, One Tree Hill, Onehunga, Otahuhu, East Tamaki and Wiri are some of the areas where large scale building of basalt walls has occurred.

Was your stone wall built in the nineteenth century?

The use of stone went out of fashion in the early 20th century, presumably after all the easily procured stone had been utilised and other materials had become more readily available.

However, more recently basalt walls have come back into vogue in some of Auckland’s older suburbs. The following images contrast the difference between a traditional pattern wall and a more recent iteration.

Contemporary stone wall

Contemporary stone wall

Traditional style stone wall

Traditional style stone wall

It can be seen that the contemporary wall is angular, the stone very close fitting, with vertical sides and is nearly 2 metres tall.

The traditional wall has battered sides and is of a more usual 1.2-1.5 metres in height. The early wall appears to have had some repairs carried out at one time and is somewhat taller at one end.

Potters Park, Balmoral

A drive around Mount Eden or Balmoral shows that traditional stone walling and later styles are still very much in evidence.

Easy to visit examples are still visible along the northern boundary of Potters Park in Balmoral.

Frederick Potter was an Auckland businessman who donated land for the park in 1916. His homestead occupied the north-west corner of the park until it was demolished in 1938.

The 3 hectares of Potters Park in Balmoral was once part of an 8-hectare allotment (no. 107) with its original eastern boundary now the rear boundaries of houses between Mewburn and Westminster Roads.

The following plan from 1907 (DP 4042) shows the area of Potters Park and its (at the time) encircling stone wall.

Images of Potters Park and other reserves

The following views are of the northern boundary of the park starting at the Dominion Road end of the wall. This end does appear to have had some remediation work at some point and has an extra course concreted to the top.

While some sections have been removed completely, the remains of the original boundary wall are visible in places as one progresses further east along the park boundary.

There are numerous other examples in public reserves such as Maungkiekie/Cornwall Park and Ambury Farm Park.

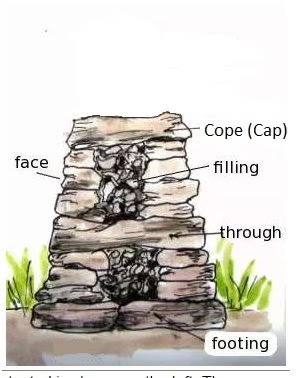

How were stone walls built?

A typical stone wall constructed for such a purpose follows a pattern common around the world.

Generally consisting of two outer battered (sloping) walls, the space between filled with smaller material and cap stones (spanning the whole wall) on top to hold the structure together.

Finished, they were commonly 1 to 1.5 metres high, a metre or so across the base and tapered to around half a metre across at the top.

Some walls, particularly taller ones have ‘through stones’ crossing the entire wall to increase stability. There were variations on this depending on material availability, purpose and the skill of a particular builder.

Walters Road boundary wall

The example shown above is a cross section of the old Walters Farm boundary wall that ran along the rear of sections on the northern side of Walters Road in Mount Eden.

It is fairly typical of the type, although thought to have been repaired/rebuilt in places in the 1920s. The right hand side of the wall has partially collapsed where a gap has been excavated through it.

Over time most walls tend to settle and bulge. They are also susceptible to being rubbed against by stock, tree roots and vibration from traffic on nearby roads. Unless particularly well built they can become unstable over time and it is not unusual for them to partially collapse.

Maintenance would involve re-fitting any loose stones and ensuring the caps were correctly fitted. Large scale repairs generally involve a few metres of the wall being dismantled to fully integrate the repair in the original pattern of the structure.

The theft of basalt stone walls

A further means of degradation is theft. There are documented instances of walls in public parks and on private property being mined for stone for landscaping elsewhere.

As a somewhat extreme example, in 2007 an entire 46 metre section of a basalt wall at East Tamaki Road, thought to date from the 1880s and on (Manukau City) Council land, was apparently stolen, or removed without the owner's permission.

To remove this much material would have needed a digger and a truck. Police were never able to resolve the case of the vanishing wall.

East Tamaki Road basalt stone wall prior to the theft.

East Tamaki Road basalt stone wall prior to the theft.

Site of the East Tamaki Road basalt stone wall not long after the theft.

Site of the East Tamaki Road basalt stone wall not long after the theft.

Legal protections

While theft is one matter, many nineteenth century dry stone walls are also archaeological in nature and are protected under the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014 (the Act).

If you’ve not heard of this legislation, the following gives a brief description of the salient points with respect to its archaeological provisions.

The Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014 provides for the identification, protection, preservation and conservation of the historic and cultural heritage of New Zealand.

All archaeological sites are protected by the provisions of the Act (section 42). It is unlawful to modify, damage or destroy an archaeological site without prior authority from Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga.

An archaeological authority is required whether or not the land on which an archaeological site may be present is designated, a resource or building consent has been granted, or the activity is permitted under regional or district plan.

According to the Act (section 6), "archaeological site" means, subject to section 42(3):

- (a) any place in New Zealand, including any building or structure (or part of a building or structure), that—

- (i) was associated with human activity that occurred before 1900 or is the site of the wreck of any vessel where the wreck occurred before 1900; and

- (ii) provides or may provide, through investigation by archaeological methods, evidence relating to the history of New Zealand; and

- (b) includes a site for which a declaration is made under section 43(1).

Archaeological authorities

An important point to remember is that while a resource consent may give permission for an activity to be undertaken under a district plan, if the activity might affect an archaeological site an archaeological authority from Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga will also likely be required to affect this.

Any dry stone wall that is demonstrably of pre-1900 origin and the fabric of which seems largely still in-situ is covered by the Act and would likely require an archaeological authority to enable modification or removal to be undertaken lawfully.

An archaeological authority ensures the site will be recorded for posterity if modified or destroyed. Recording confirms materials used, construction technique and from time to time recovers artifacts left in the wall by whoever built it.

Where pre-1900 age is confirmed, the need for an authority is determined on a case-by-case basis following review of an assessment of effects on its archaeological values.

If you are unsure about the age of your dry stone wall and you need to repair, modify or remove it you should contact your nearest Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga office and speak to the archaeologist for that area for assistance. There is no cost to property owners to consult with us on such matters.

If you require any further information on archaeology or heritage in general please don’t hesitate to visit our website.