PHOTOGRAPHER TRANSFORMED

To celebrate the inaugural Documenting Our Heritage Photography Competition, we interviewed Dunedin street photographer Mark McGuire.

Images: Mark McGuire

Quotes: Mark McGuire Street Photography

“The result of street photography is not a photograph; the result of street photography is a transformed photographer.”

How can photography—specifically street photography—transform the photographer? How has it transformed you?

Mark: Street photography is one way to learn how to be fully present in a place, and to be open to whatever you find there. The photograph serves as a reminder of an experience you had at a particular place on a particular day. The photograph isn’t the experience itself, but a souvenir. A souvenir can be treasured, too, but only to the extent that it is linked to a significant, meaningful experience.

Street photography has helped me to see rather than just look. It has helped me to notice the importance of small, incidental details in our urban environment, and to see beauty in the ordinary and the everyday. Grand, national narratives are built from small, personal stories.

“Visitors don’t come to a city to be present and alive anymore, they come to perform their dramatic escape. Special jumping-off points with impressive backdrops make the act of leaving a memorable event.”

How do you think contemporary photos of departure compare to historic departure images (such as those by John Rykenberg) and do you think this has had an impact on the physical spaces?

MARK: John Rykenberg’s photos document relationships between people at a significant site of departure — the Auckland wharves. His photos memorialise the face-to-face relationship between the photographer and the people photographed, and the strong, soon-to-be-distant, relationships between departing passengers and their whānau.

When we want to travel these days, we are more likely to go online than board a liner. We might document our departure from the physical world with a selfie taken in front of a background built specifically for the purpose. Alas, the streamers we see upon our arrival on the social media platform of our choice are pixelated and fleeting.

For those who really want to go out in style, there’s a book currently available in local shops called Take Your Selfie Seriously: The Advanced Selfie and Self-Portrait Handbook. It would be funny if it wasn’t so sad.

Online, we are encouraged to see ourselves as brands pushing products, rather than as individuals with a story to tell. Social media facilitates transactional, rather than personal, relationships. You heart me and I’ll heart you. Follow, follow back. DM for prints.

“Like an empty chair on the roadside, a broken umbrella stuffed into a trash can, or a dropped glove flattened on the pavement, an abandoned shopping cart encourages us to contemplate the human condition.”

How does a photographer transfer these spontaneous moments of contemplation into the final image, especially when working in an uncontrolled, unpredictable public space?

MARK: In the hustle and bustle of urban environments, it’s hard to see through the noise. We must look for the gaps, pauses, and silences. That’s where meaning settles. Empty spaces and vacant buildings are full of stories worth finding and sharing. Spend some quiet time in a party room after all the guests have left and have a close look at the room, the decorations, and everything else that’s been left behind. Take your time. You’ll see what I mean.

"A street is a storyline that you enter in the middle. There’s no script, no editor, and no one giving stage directions. You can be a participant, a spectator, or both."

What role does story play in your photography, both in individual photos and collections or series?

MARK: As the novelist, Thomas King, wrote, “The truth about stories is, that's all we are”. And as the graphic designer, David Carson, likes to say, “you cannot not communicate”.

We are hearing, reading, telling, retelling, and remixing stories all the time. We can’t run from stories any more than a bird can fly from air. Some stories seem more unintelligible and confused than others, but all stories are partial. We spend a lifetime trying to put our story together. Photography, like other forms of creative expression, is a necessary, and necessarily unfinished, effort to engage in a shared conversation through storytelling.

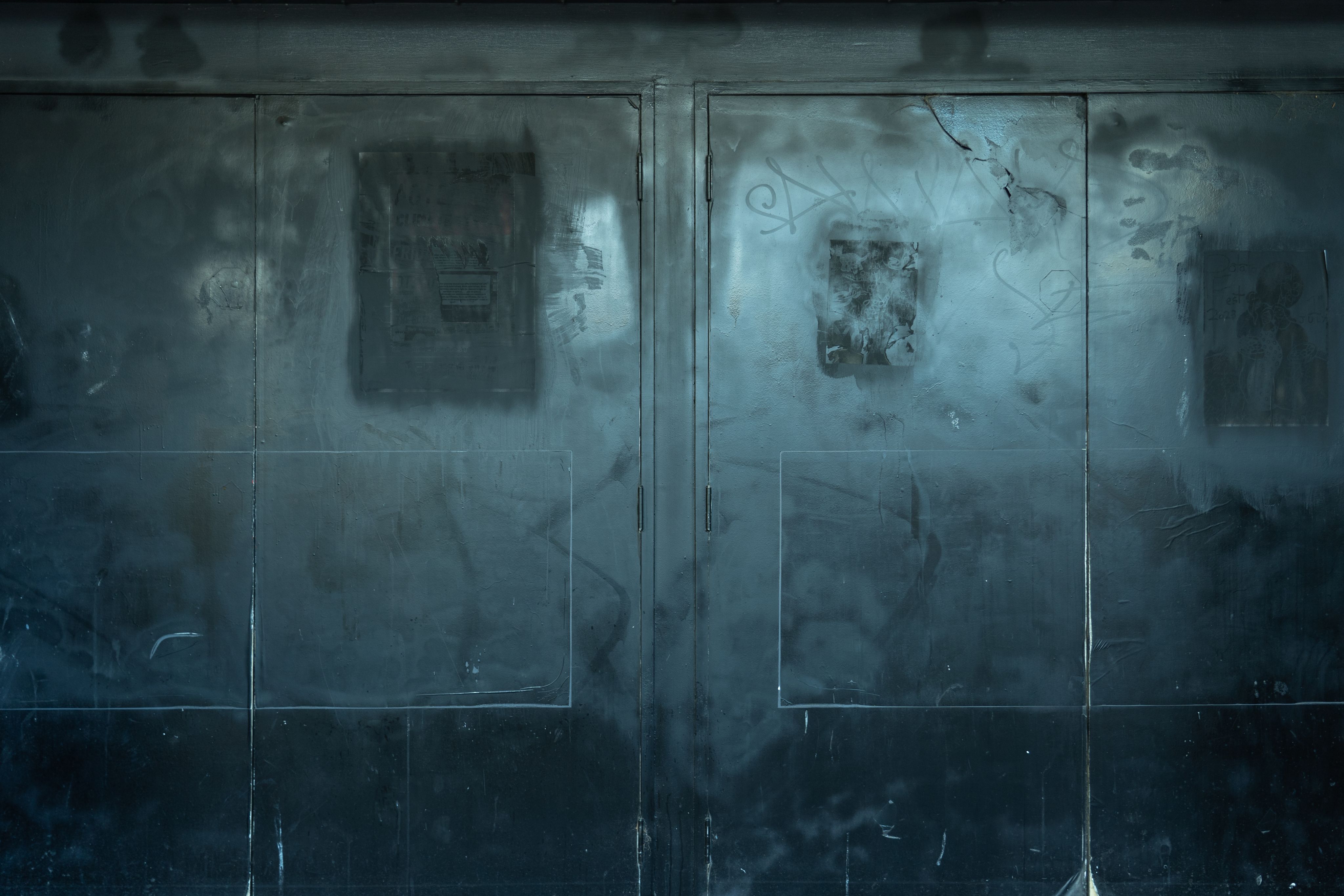

“I could tell you a story about these buildings... I could tell you about how the Dunedin City Council would like the historic facades to be retained. Or about how the owners/developers have let them fall into ruins... But instead, I was attracted, on that grey day, by the vibrant colours of the orange plastic safety fencing and the graffiti on the rotting walls behind.”

How can contemporary street photography complement recorded (and often official) histories of buildings and places?

MARK: It’s been said (by many photographers) that all portraits are self-portraits. Indeed, every photograph reflects the desires, fears, memories, and emotions of the photographer.

Anyone who carries a smartphone is a potential street photographer. These days, that’s almost all of us. Every day, we record our personal account of the world as part of our lived experience. Almost incidentally, these include our take on the places and buildings around us. If only these reflections, as many and varied as we are, could be brought together. Imagine the stories they could tell.