Rongo Hongi

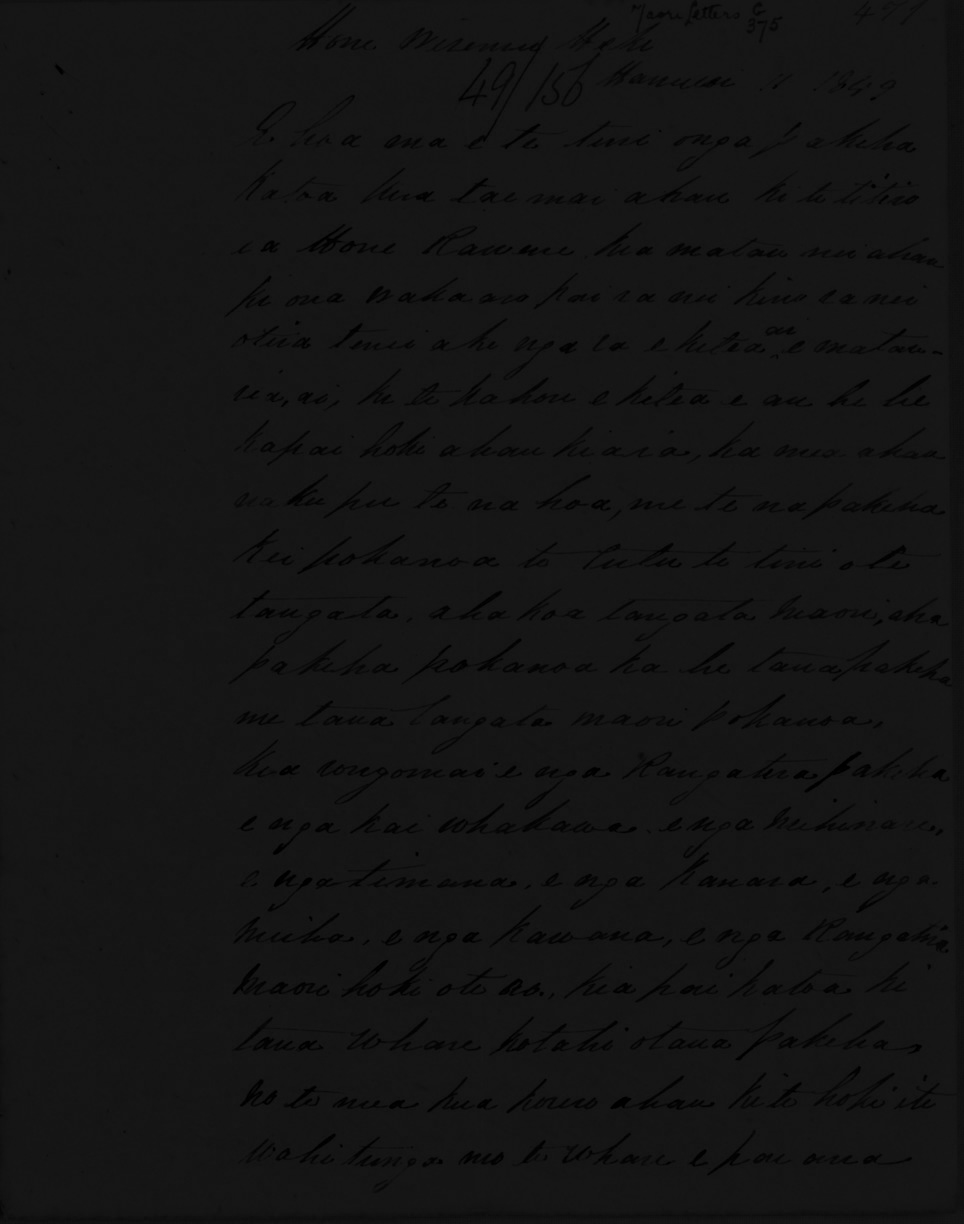

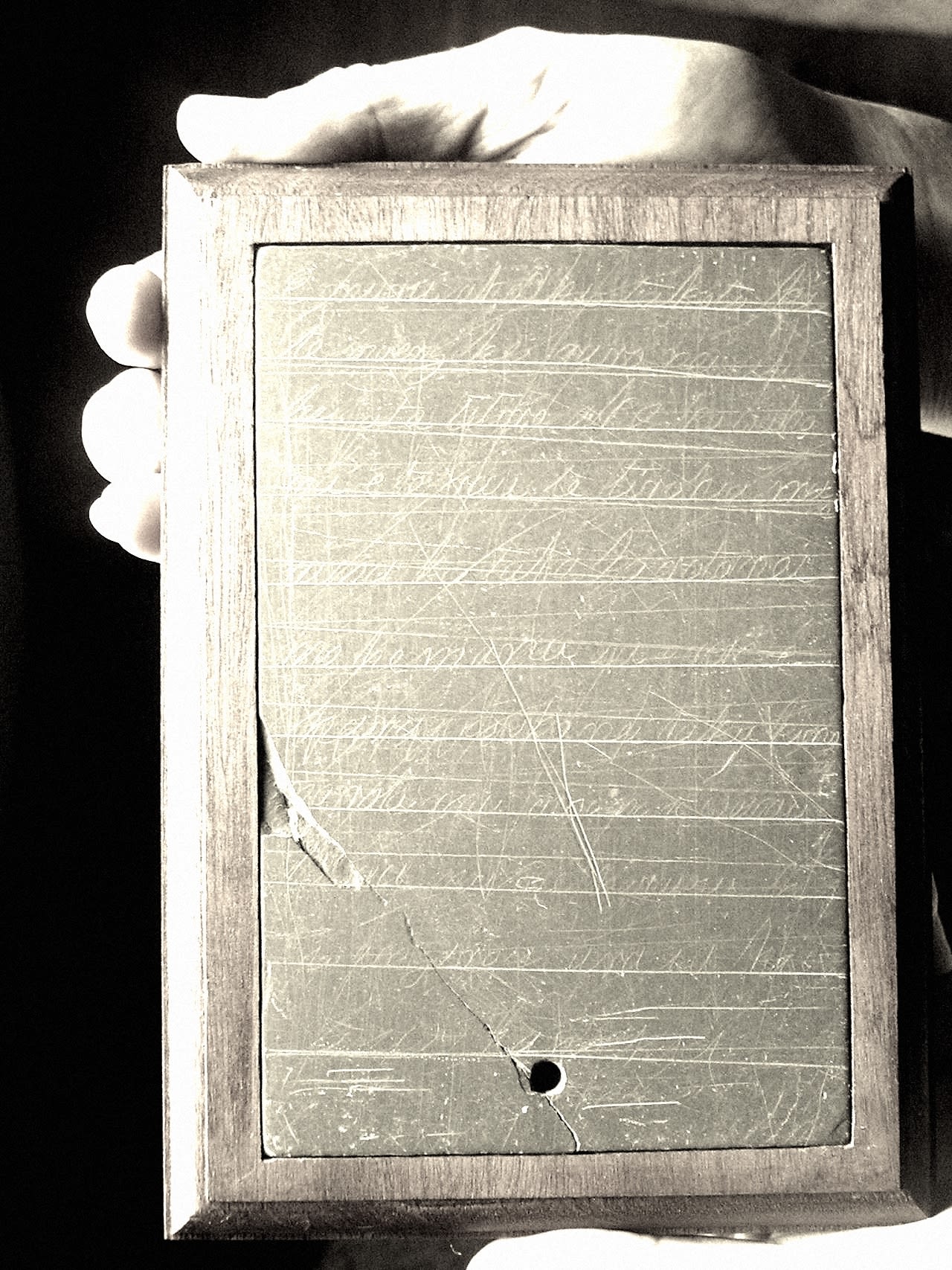

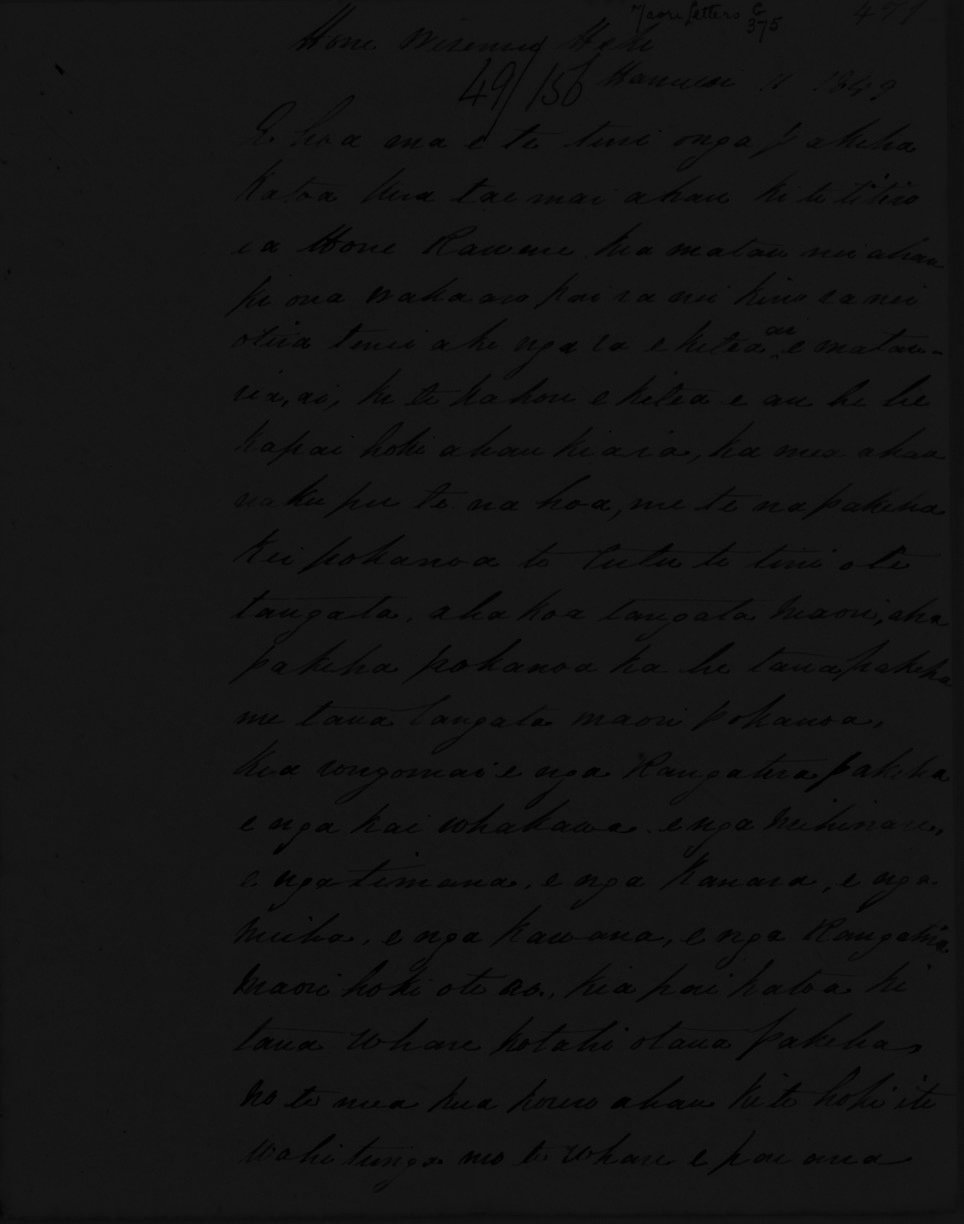

The Origin of the Kerikeri Mission Station Slates

June 21, 2000, started as a normal day for Fergus Clunie. An advisor at the Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga), Fergus was at Kemp House in Kerikeri Mission Station, investigating the building's support system.

Working on Kemp House wasn't an easy job: at 178 years of age (in 2000), it was the oldest building in the country. But Fergus had undertaken similar projects before. He knew what to expect.

One-by-one, he lifted the pantry floorboards. He could see earth. He could see piles. And tucked away in the darkness, he could see something else.

Writing slates. And it looked like someone had tried to hide them.

The writing slates that Fergus discovered were small, measuring just 21cm by 15cm. Carved into one was a waiata whakautu, a song of reply to an accusation. On another was a name and age.

"Na Rongo Hongi, 16".

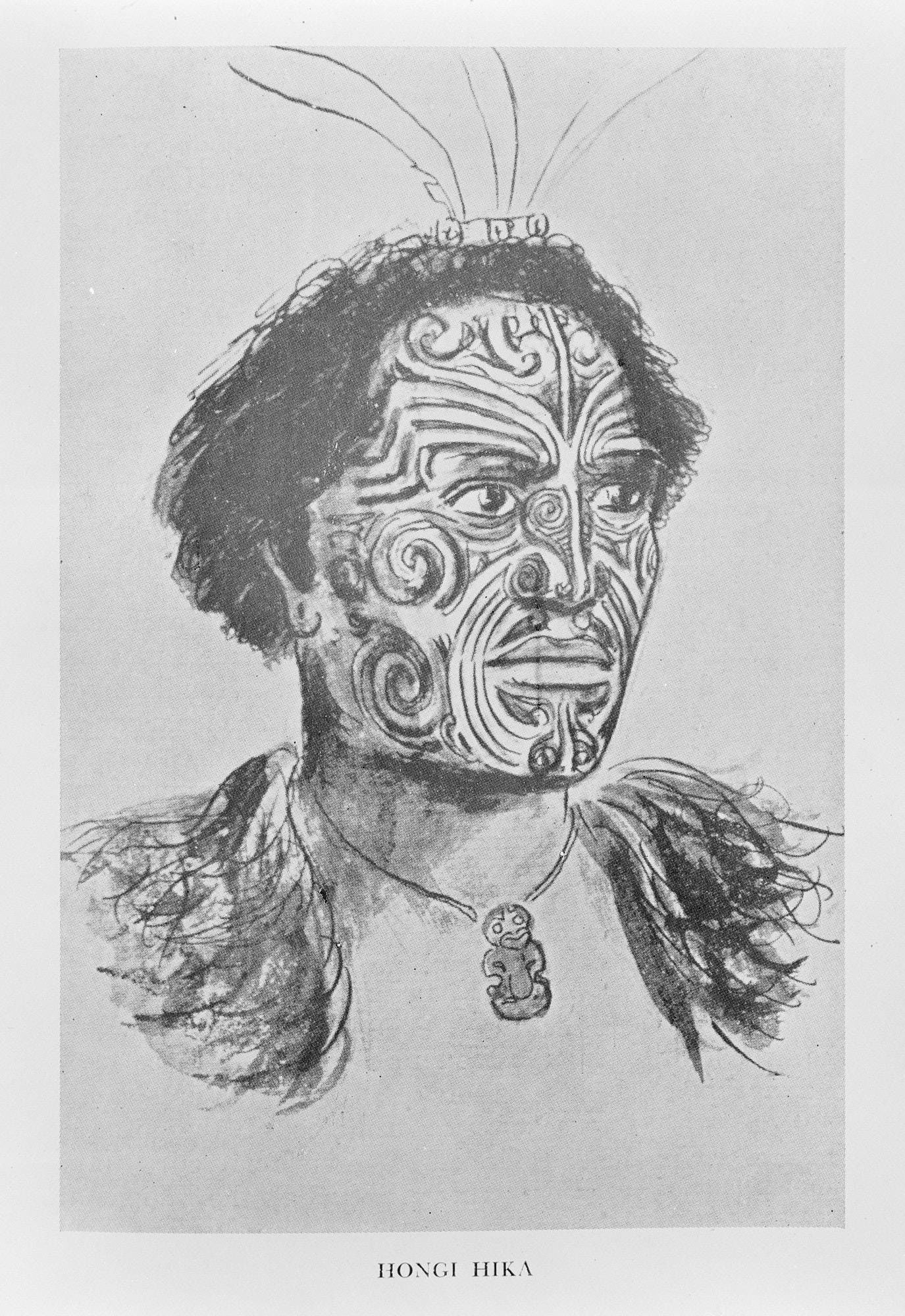

Fergus knew the find was significant. Rongo Hongi was the daughter of two Ngāpuhi rangatira: Hongi Hika and Turikatuku, a wāhine of considerable mana.

"I doubt we could have come up with a more evocative historical item than [Rongo's] slate had we tried," Fergus said in a New Zealand Herald article published not long after the discovery.

To understand exactly why Rongo's slate is so important, you have to return to the year of her birth, over two centuries ago.

Back to 1815.

"I knew the age of this little girl, for she was born at [Okuratope]... the very night I slept there when first in New Zealand."

Samuel Marsden on the birth of Rongo Hongi

When you imagine Aotearoa in the early nineteenth century, you might picture it like this: a cluster of islands at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

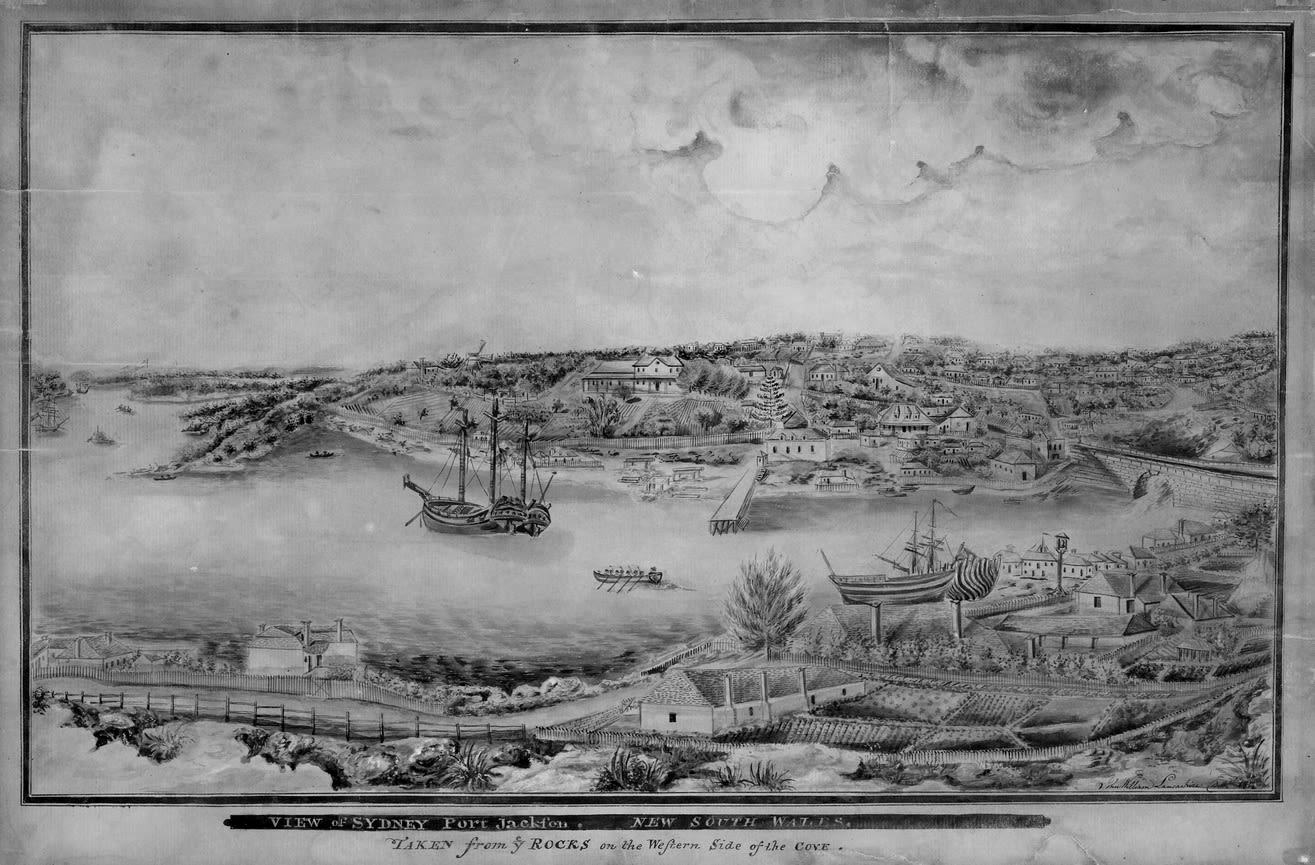

But in fact by 1815, Aotearoa was already connected to a much wider world. Ngāpuhi rangatira Te Pahi travelled to Poihākena (Port Jackson) in 1805. Hongi Hika would visit in 1820.

View of Sydney Port Jackson, New South Wales, ca. 1803. Drawn by John William Lancashire. Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales.

View of Sydney Port Jackson, New South Wales, ca. 1803. Drawn by John William Lancashire. Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales.

Others ventured further. Moehanga (Ngāpuhi) discovered the city of Rānana—also known as London—in 1806. Hongi Hika would follow in 1820.

Queen Square, London, ca. 1790. Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons 4.0.

Queen Square, London, ca. 1790. Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons 4.0.

Back in Aotearoa, Hongi and Turikatuku had a different plan for their daughter.

Rongo didn't need to travel to Port Jackson or London to learn about the world. Instead, her parents would bring the world to her.

Kerikeri Mission Station

Kerikeri Mission Station was established in 1819, the result of a fortuitous meeting between Hongi Hika and CMS missionaries at Port Jackson five years earlier.

Missionaries were a valuable resource in early nineteenth century Northland: they provided a link to trade—and muskets—that would propel taua south for years to come.

Hongi Hika, 1820. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 7-A10088.

Hongi Hika, 1820. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 7-A10088.

But mission stations had another purpose: a source of knowledge.

Between 1824 and the mid-1830s, Rongo spent significant time with Charlotte Kemp, wife of missionary James Kemp, at her school at Kerikeri Mission Station. Of all the skills Rongo learnt there, the most important was writing.

That’s where the slates come in.

It was on the Kerikeri Mission Station slates that Rongo wrote her first sentence. It was on these slates she discovered the strengths—and limits—of the written word.

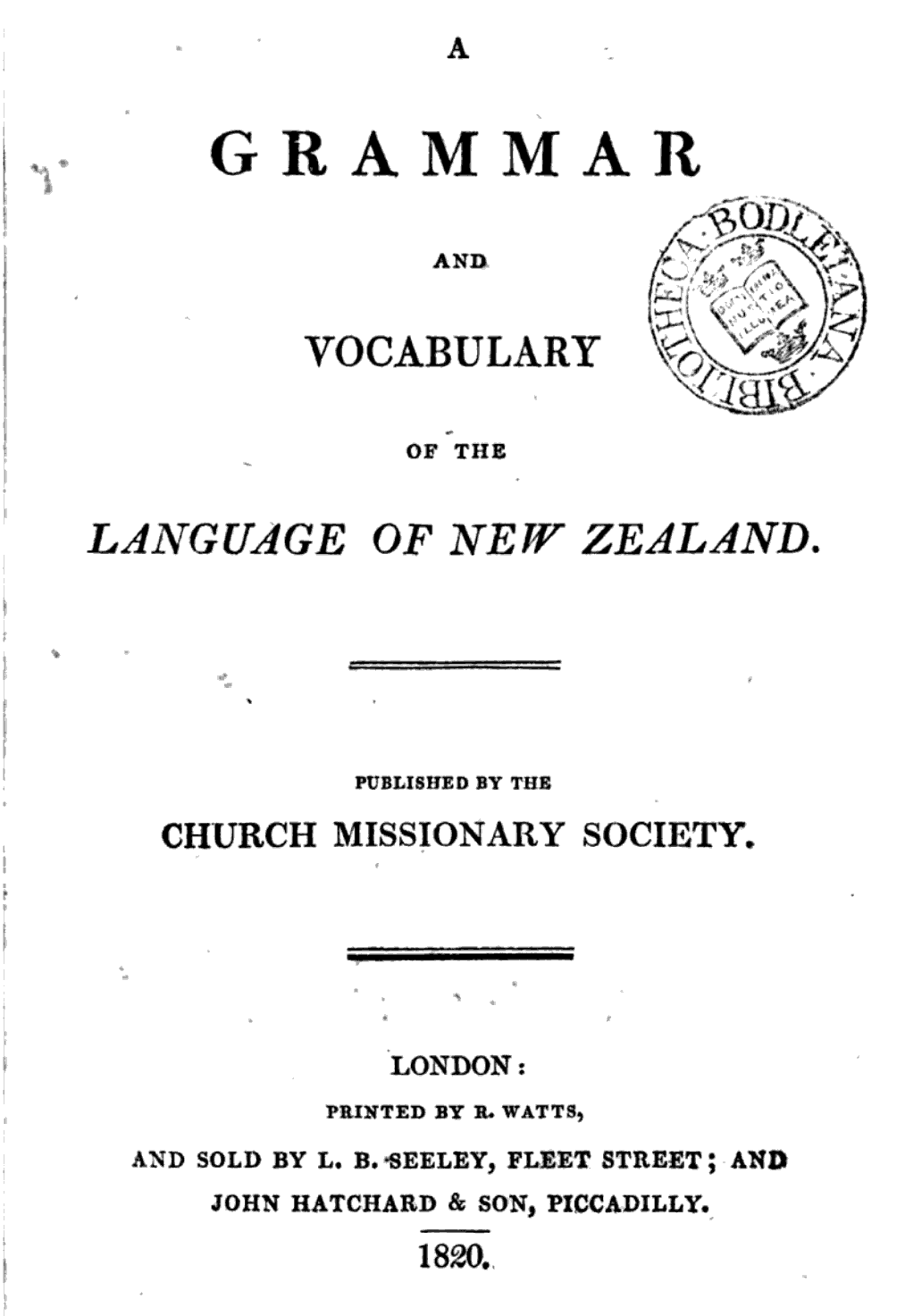

The dictionary created by Hongi Hika while visiting Cambridge, England in 1820.

The dictionary created by Hongi Hika while visiting Cambridge, England in 1820.

Rongo’s time with the Kemps was just one part of her education as a rangatira. When she wasn't at Kerikeri Mission Station, Rongo accompanied her father on trading trips to Kororāreka; she marched south with her mother to war.

Then in 1831, Rongo fell ill. She was brought to Kerikeri Mission Station where her arrival was noted by James Kemp:

"She is the youngest daughter of the last Hongi... She has been very near death’s door."

Rongo survived—just. But things were changing. By 1831, she had lost her father, mother and two siblings. Northland's population was growing: not just missionaries but whalers, grog sellers, men in search of land.

Whatever came next, Rongo was ready.

"Land? Not by any means, because God made this country for us; it cannot be sliced, if it were a whale it might be sliced."

Letter from Hariata Rongo and Hōne Heke to Governor Grey, 1845

Dawn, 11 March 1845. The settlement of Kororāreka is waking. A dog barks; a Royal Navy ship creaks in the harbour. On the nearby hillside sits a newly-built blockhouse.

Then: gunshots from the south. The 96th Regiment troops stationed in town advance towards the noise. Figures move in the shadows. Another gunshot, a yell.

Little do they know, it's a diversion.

While British troops chase ghosts, several hundred Ngāpuhi soldiers approach the blockhouse. At their head is none other than Hōne Wiremu Heke Pōkai.

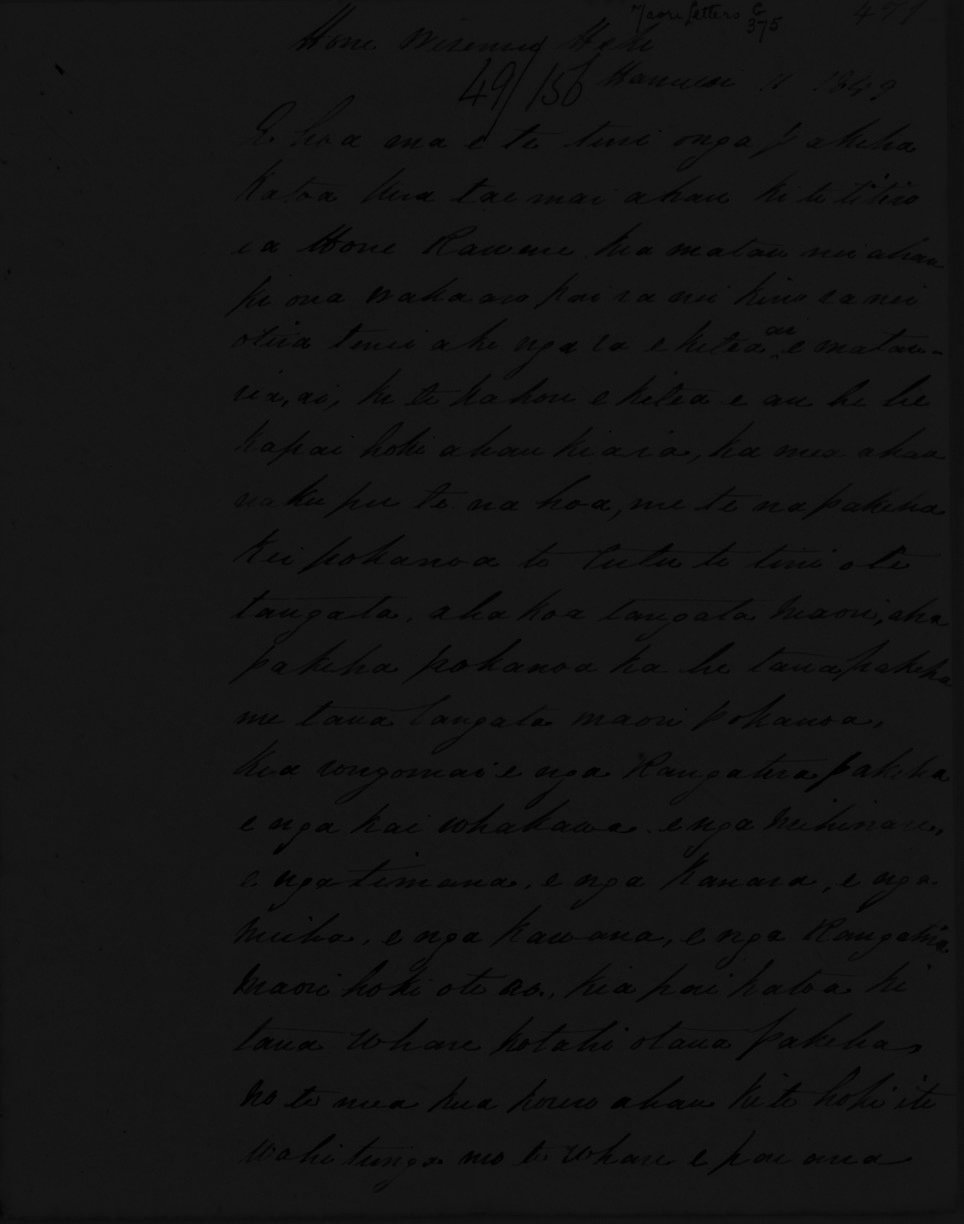

Hōne Heke, from The New Zealand Wars by James Cowan. Pencil drawing by J.A. Gilfillan.

Hōne Heke, from The New Zealand Wars by James Cowan. Pencil drawing by J.A. Gilfillan.

Heke captures the blockhouse, then turns his attention to a nearby pou. It's his pou, the fourth established on this spot. It's meant to fly the flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand, but today it carries the Union Jack.

Heke approaches. With several powerful strokes, his soldiers bring the pou down.

Below him the fighting continues. Gunpowder stores explode; the naval vessel fires into the streets. Kororāreka burns.

The destruction of Kororāreka was a tipping point in many people's lives, not least for Rongo. There were several reasons for this, including a personal one:

Hōne Heke was her husband.

Rongo and Heke had married in 1837, with the pair moving to Kaikohe before Rongo’s baptism on 26 January 1840. From this point on she would be known by her baptismal name, Hariata.

Eleven days later, the pair would reach Waitangi. Beneath the spars and sails of a makeshift tent, Heke—no doubt after kōrero with Hariata—signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Te Tiriti was unequivocal: rangatiratanga remained with Māori. The powers of the Governor, a sickly naval officer named Hobson, would extend as far as land-hungry recent arrivals.

But by 1845 this sovereignty was under threat. The Crown, now based 240km south in a garrison town named after Lord Auckland, was an increasing threat to trade. Uncompromising colonists ignored Māori law.

Commercial Bay, Auckland, 1843, Edward Ashworth. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Commercial Bay, Auckland, 1843, Edward Ashworth. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Heke and Hariata knew the truth: these actions weren’t accidental overreach—they were the tip of an iceberg. Heke's felling of the pou was a response to this, a symbolic challenge to the creep of imperialism.

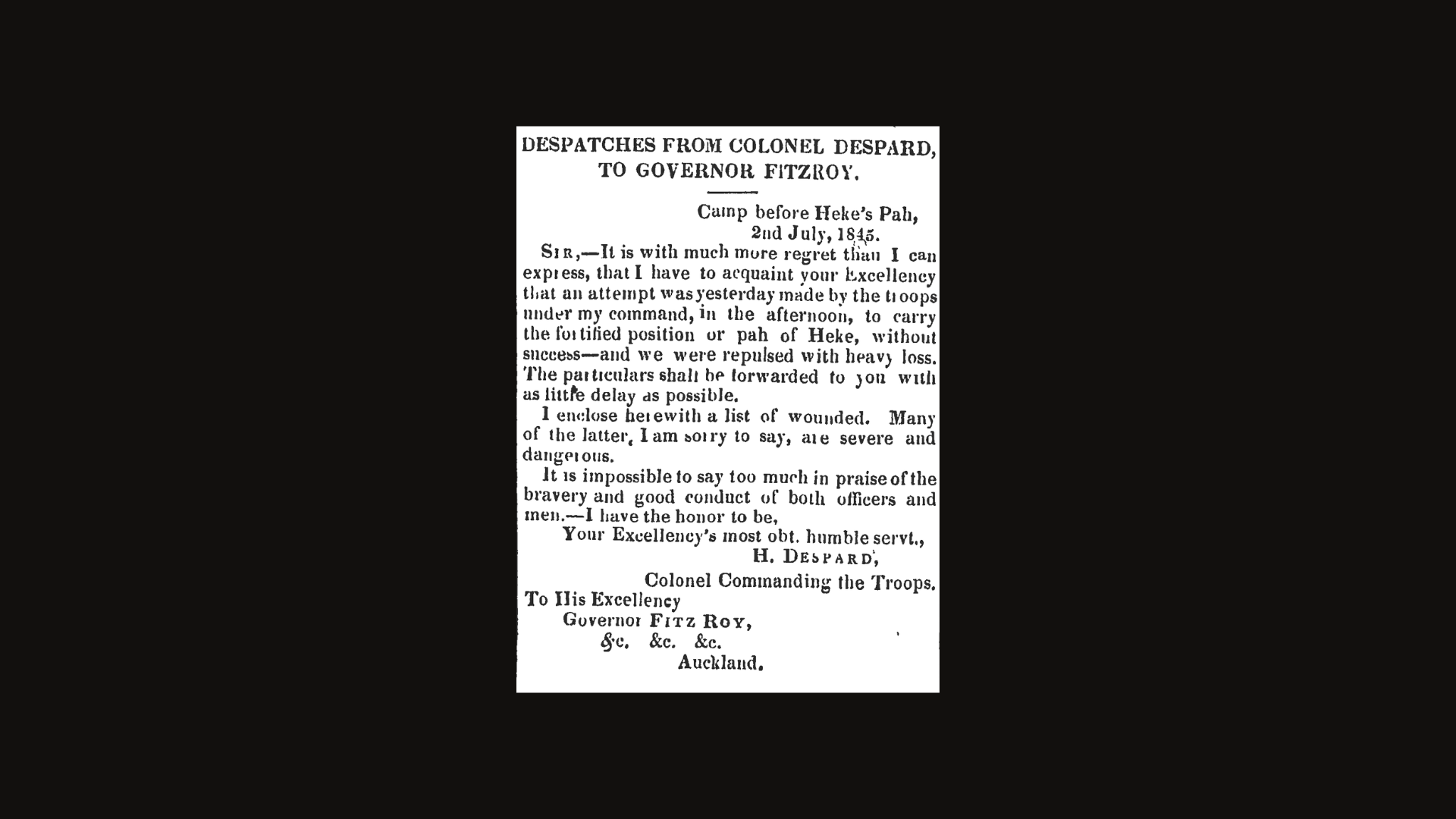

Symbolic or not, the assault provoked a reaction. Governors Fitzroy and Grey called up hundreds of British soldiers. With them came cannons, mortars and the terrifying Congreve rockets.

War had broken out—and Hariata was in the middle of it.

(Background image: "Kororāreka before the assault", 1845. Creative Commons 2.0.)

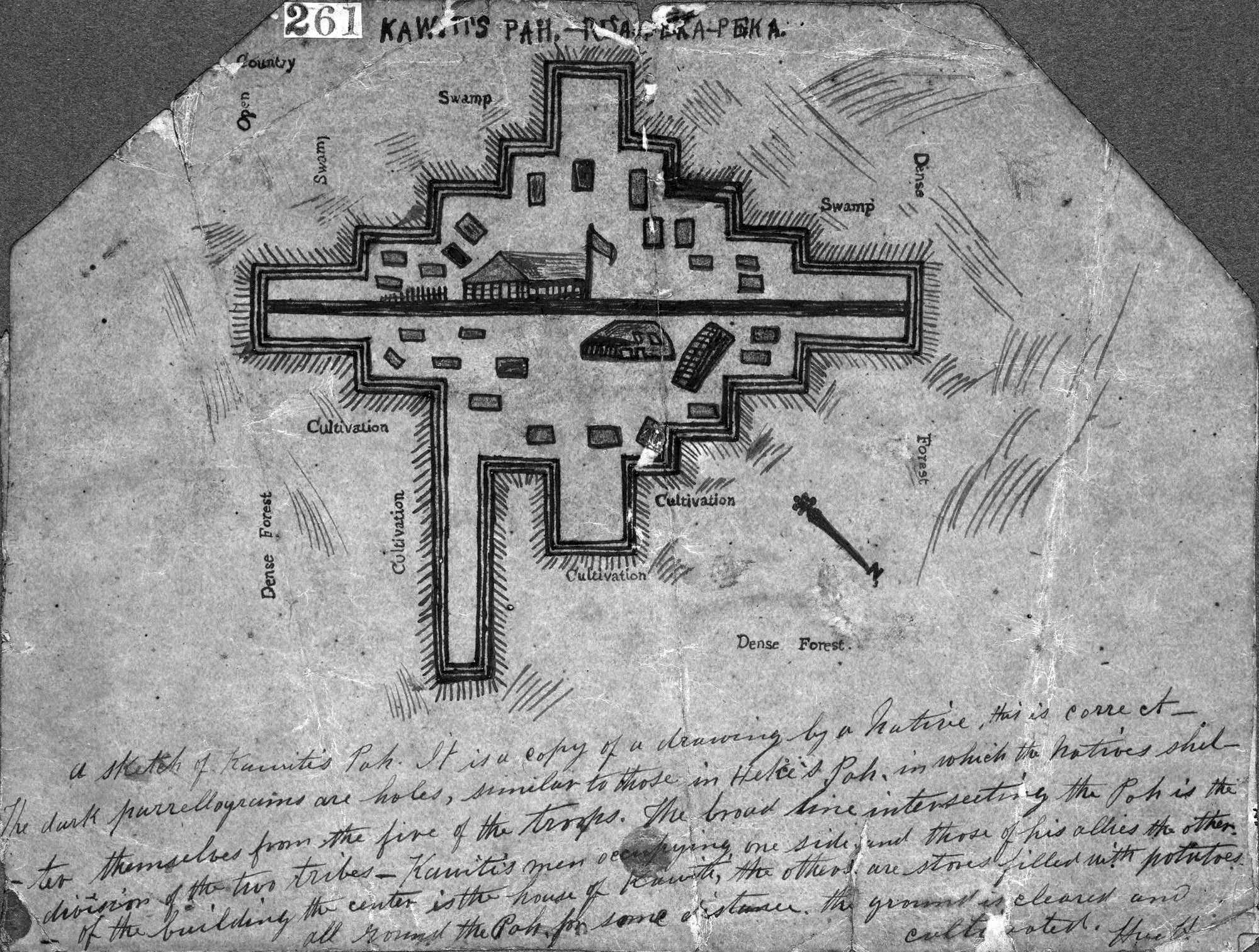

A lot has been written on the innovative pā of Te Ruki Kawiti and Hōne Heke. However, what is less well known is that while British regiments were heaving their cannons towards the palisades, another battle was going on—this one involving the written word.

Ruapekapeka. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 4625.

Ruapekapeka. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Map 4625.

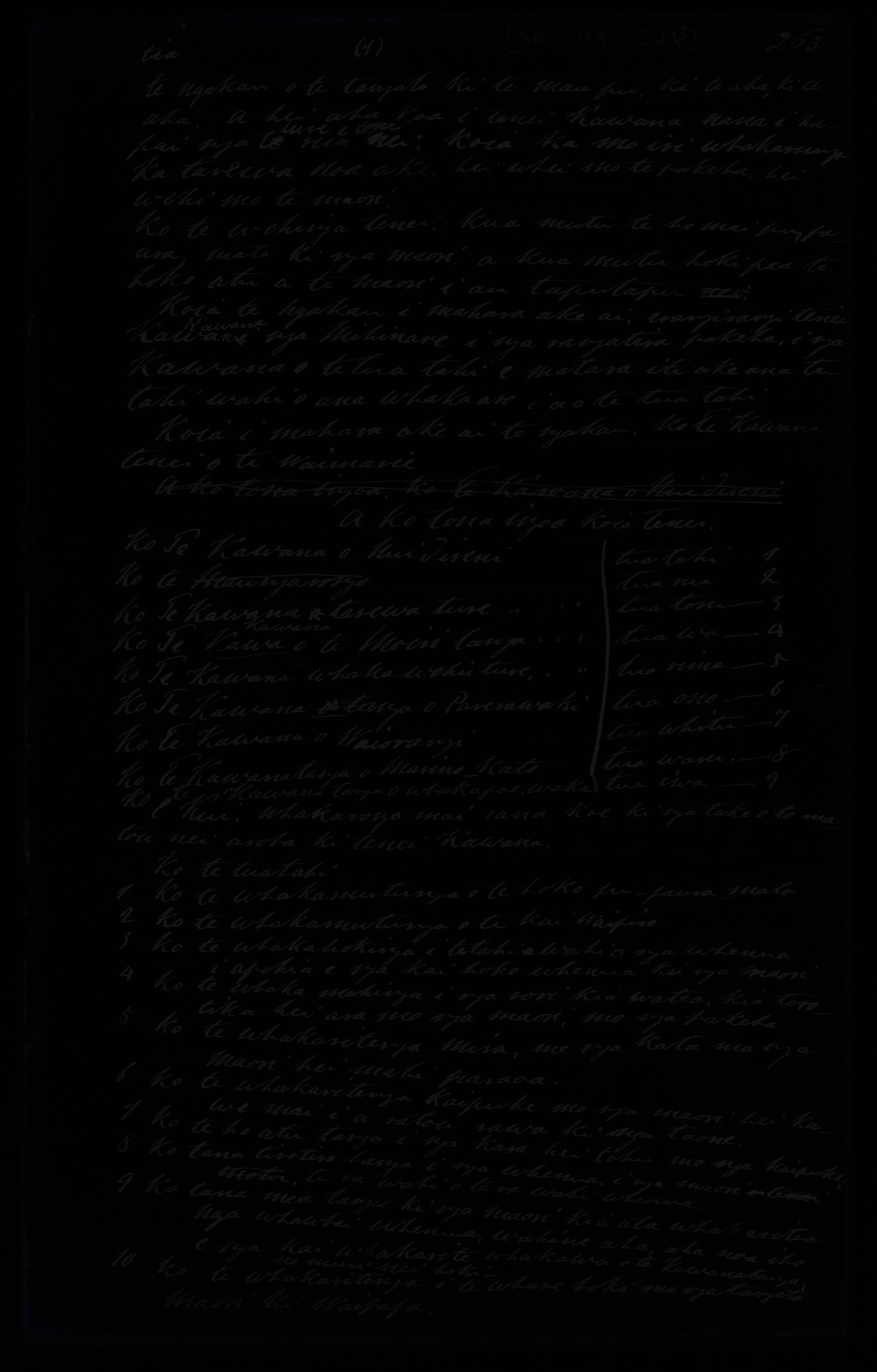

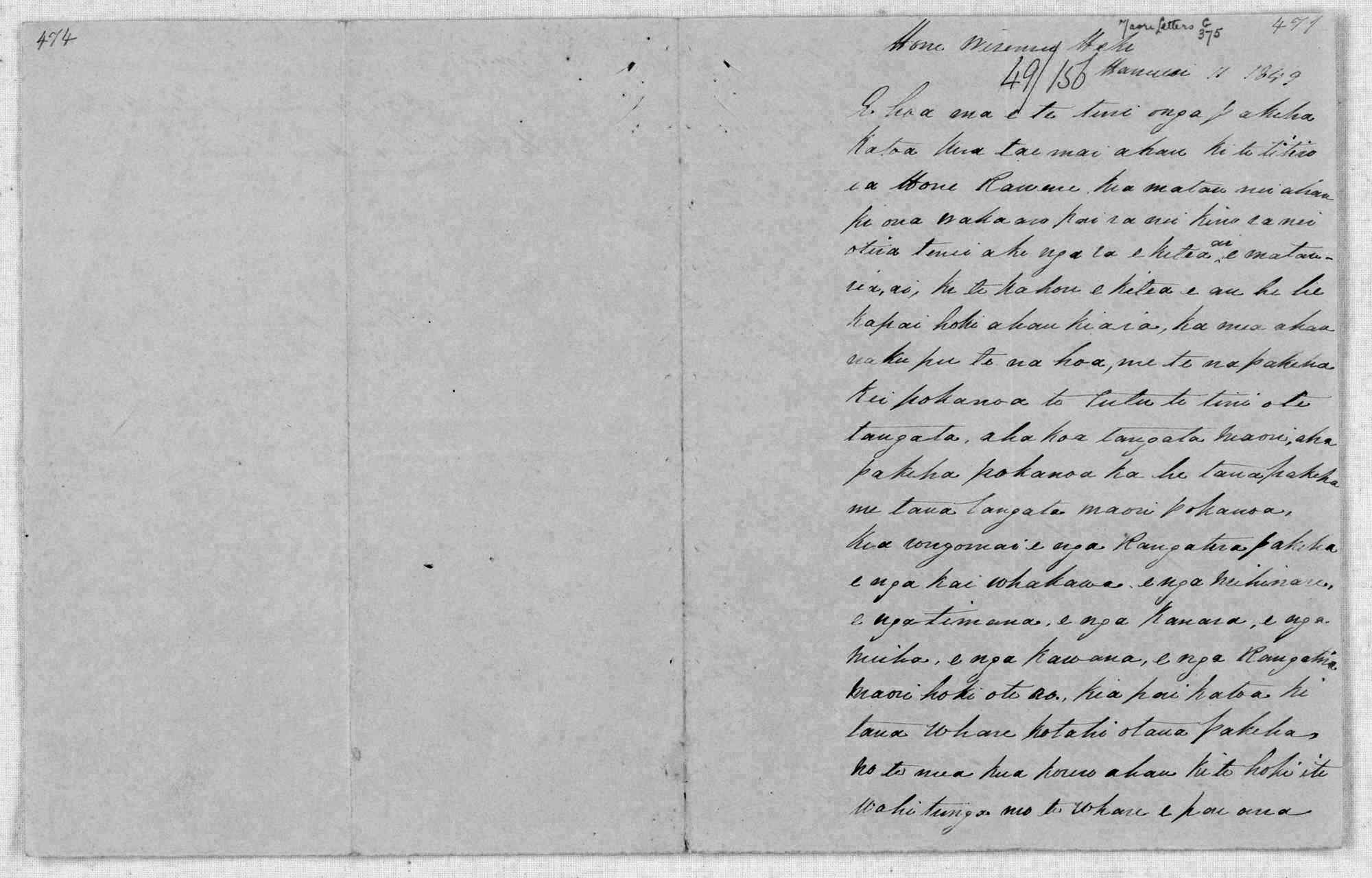

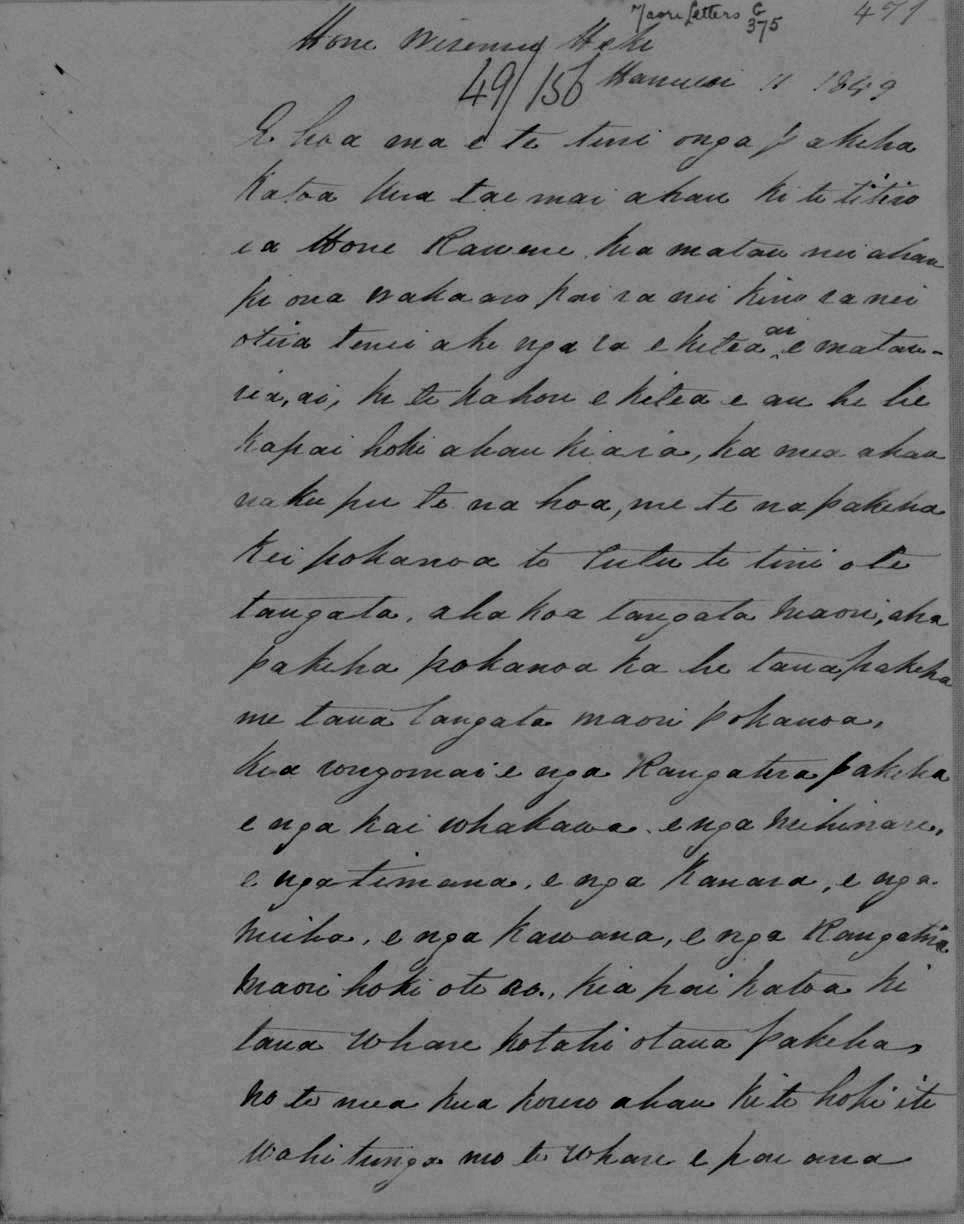

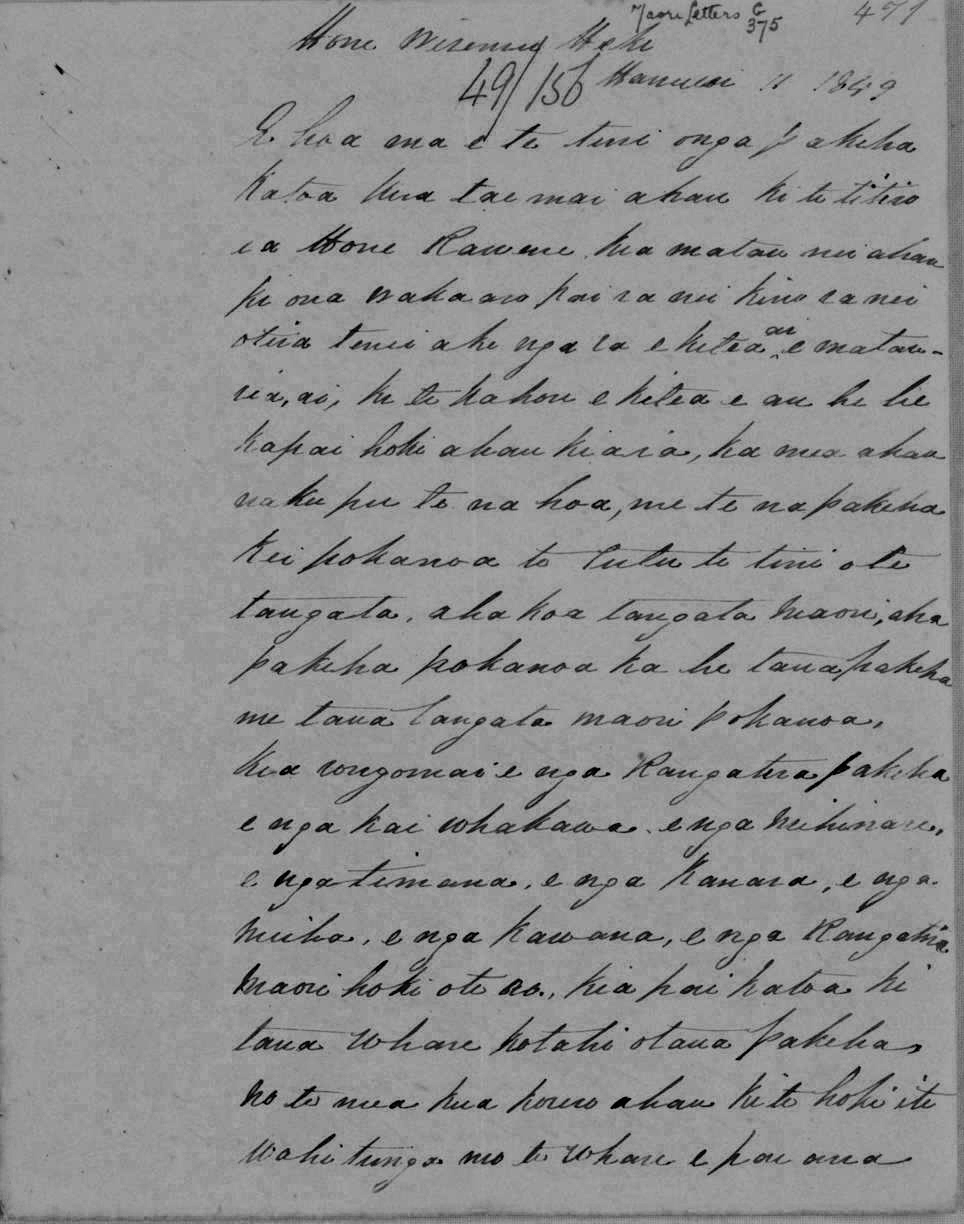

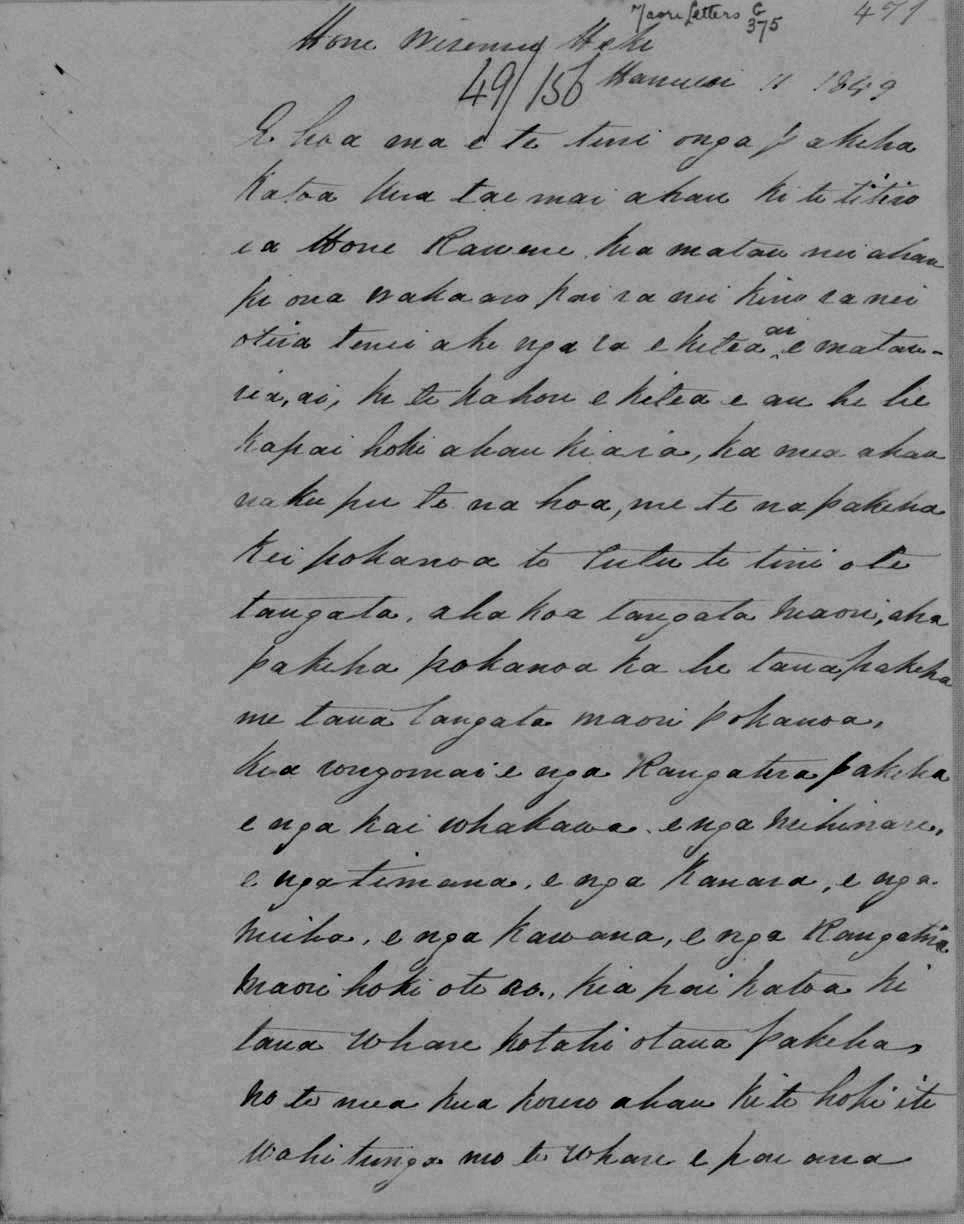

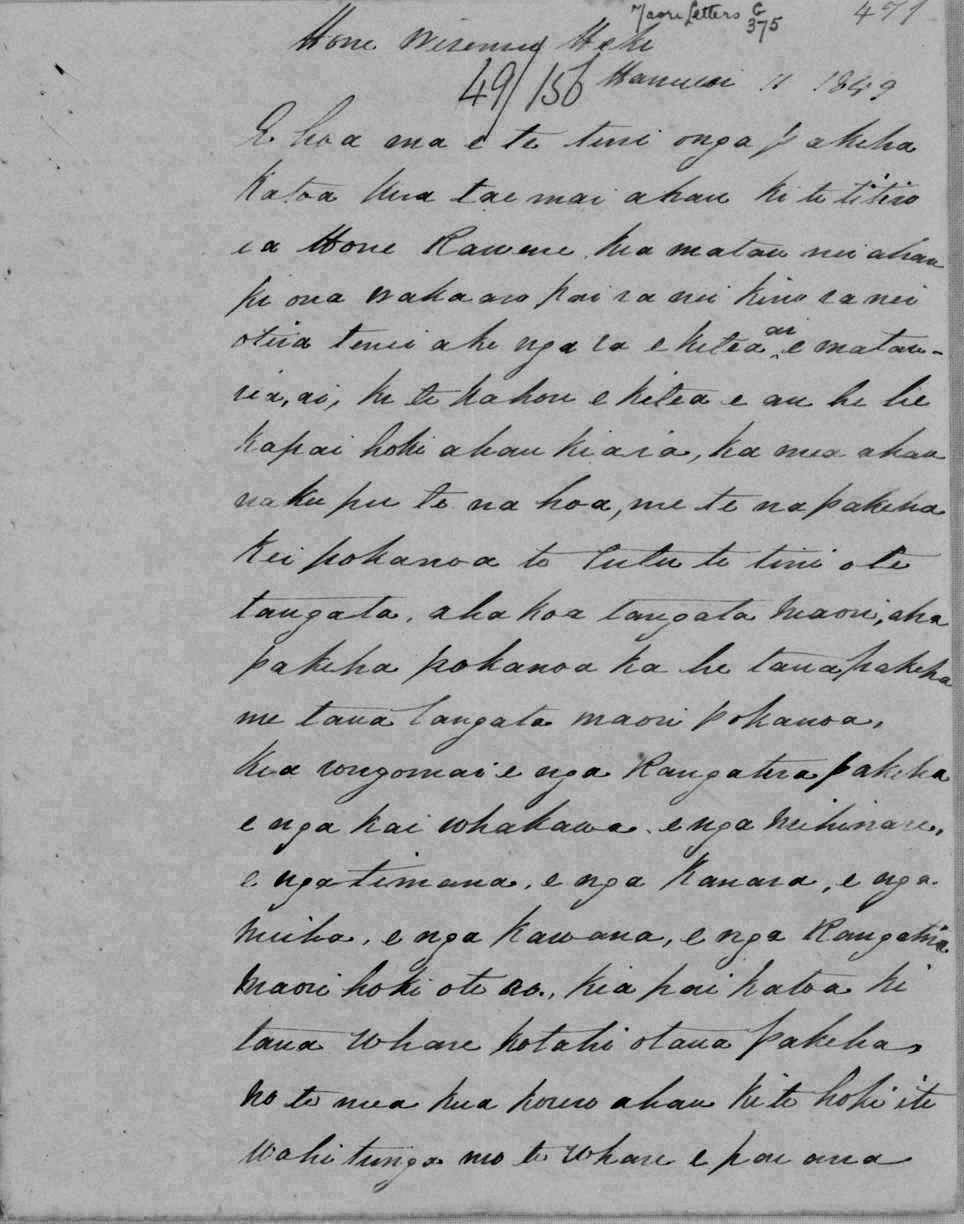

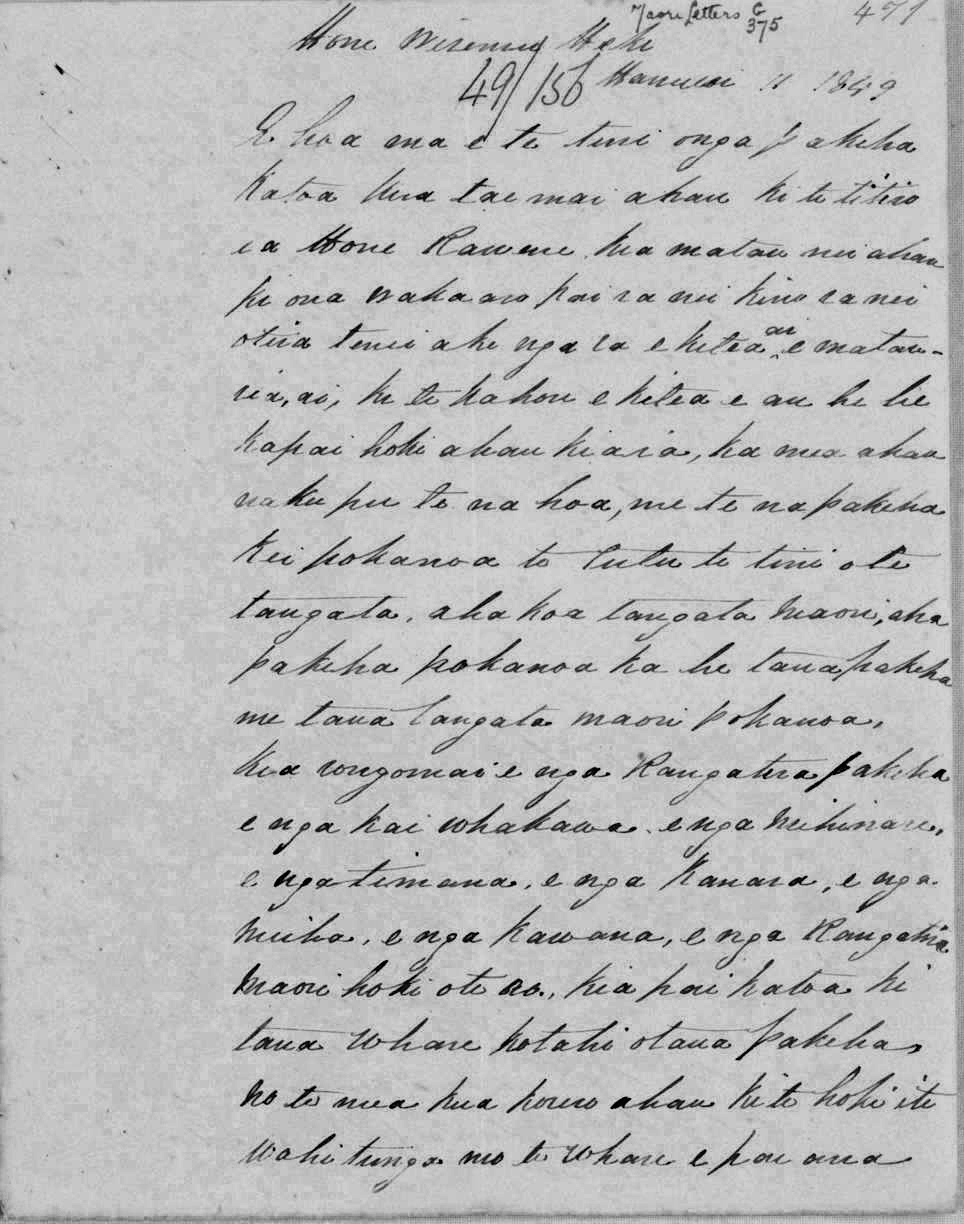

Between 1844 and 1850, Hariata and Heke sent a series of letters to Governors Fitzroy and Grey in an attempt to influence the war and its aftermath. These weren’t dry diplomatic documents, they were letters designed to engage, challenge and explain.

And they were often successful.

The most well-known of these is “How oft bitter words fall needlessly from the lips”, sent to Governor Grey in 1849. In it, Heke (and likely Hariata) wrote:

Thine fine words only have arrived

In order I might trust thou is inclined my way

The dividing line was at Auckland

And stormy winds blew upon Tautoro

Here is an end to the days of listening

(Translation by Governor Grey and Sir Apirana Ngāta.)

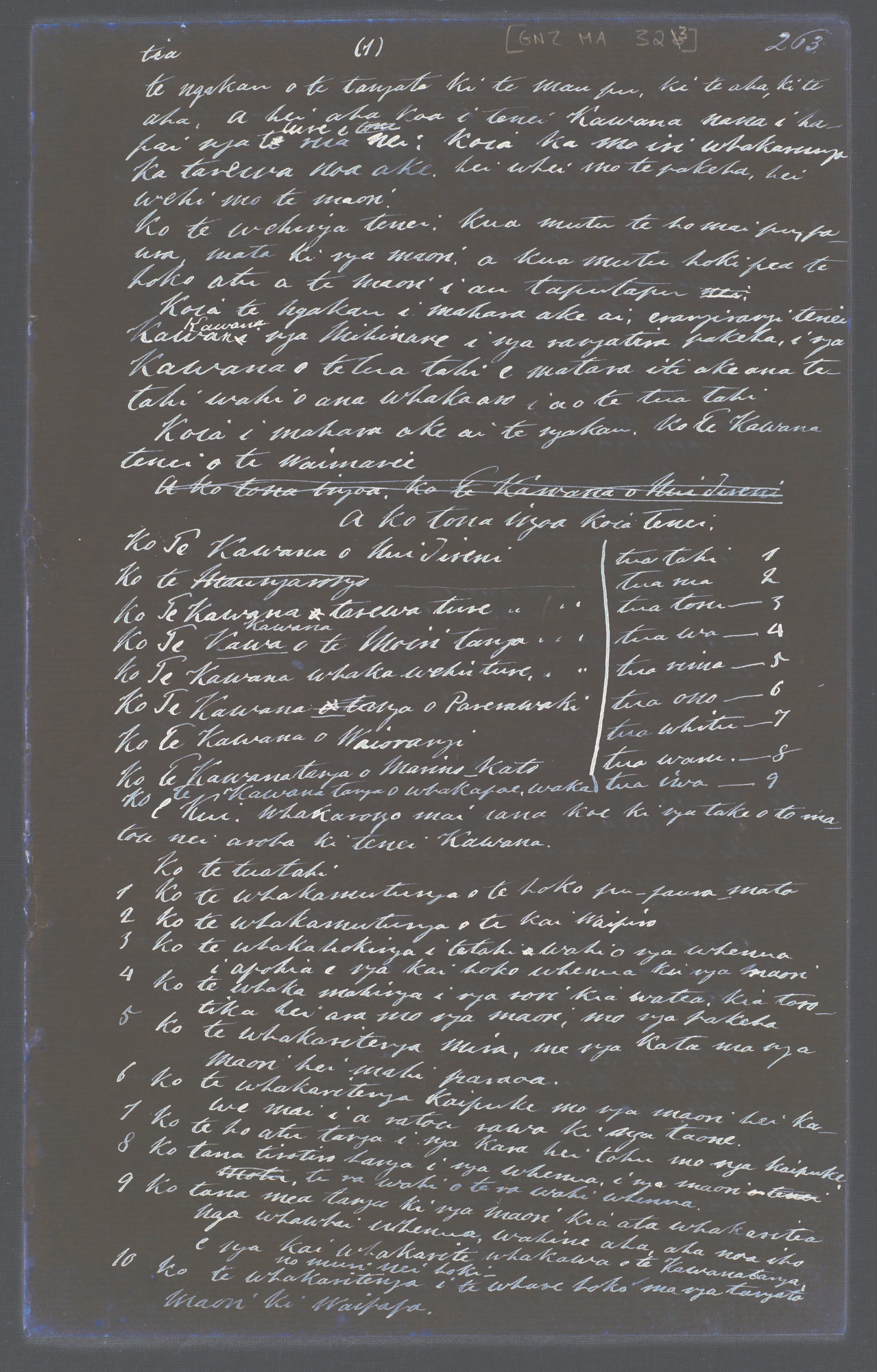

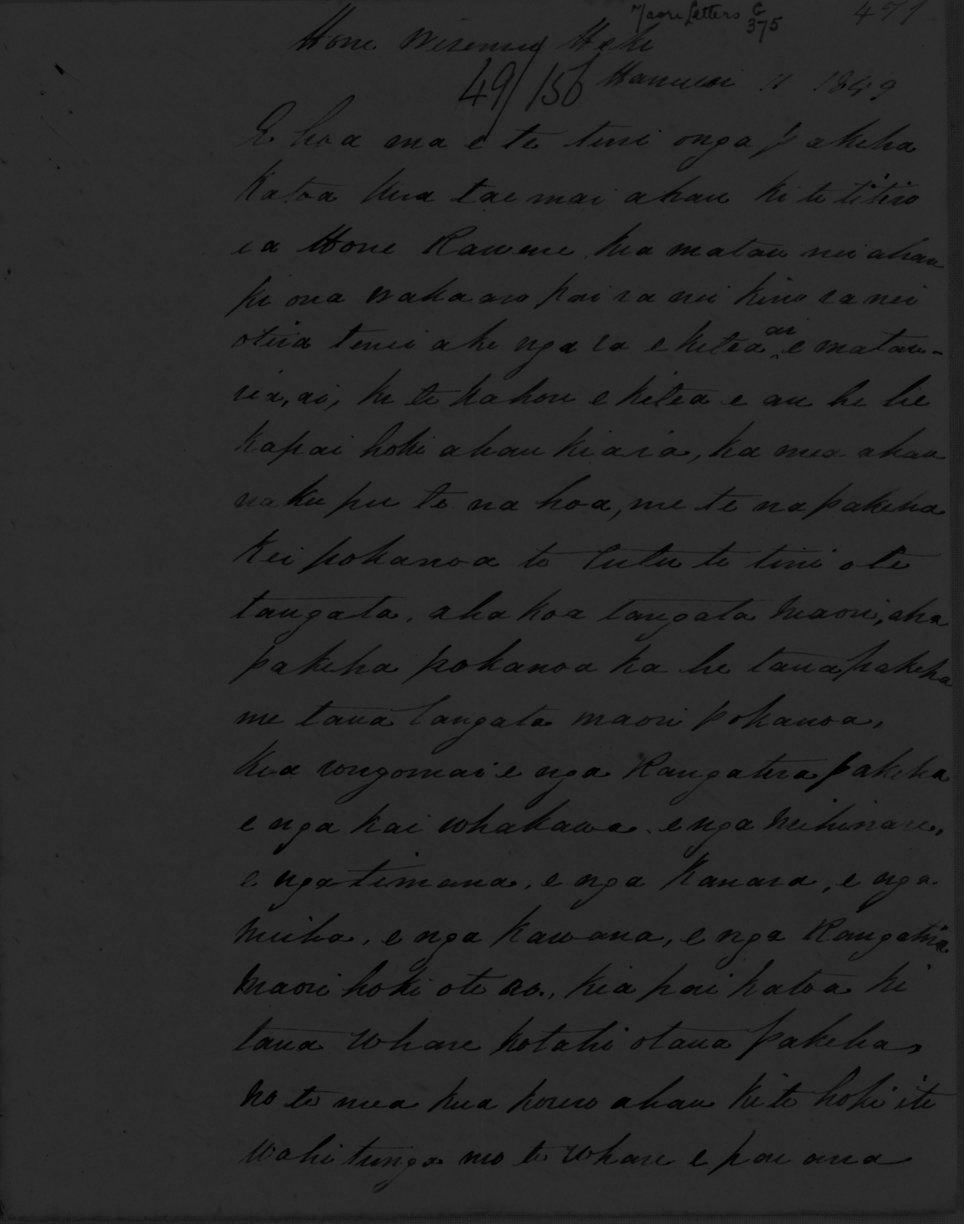

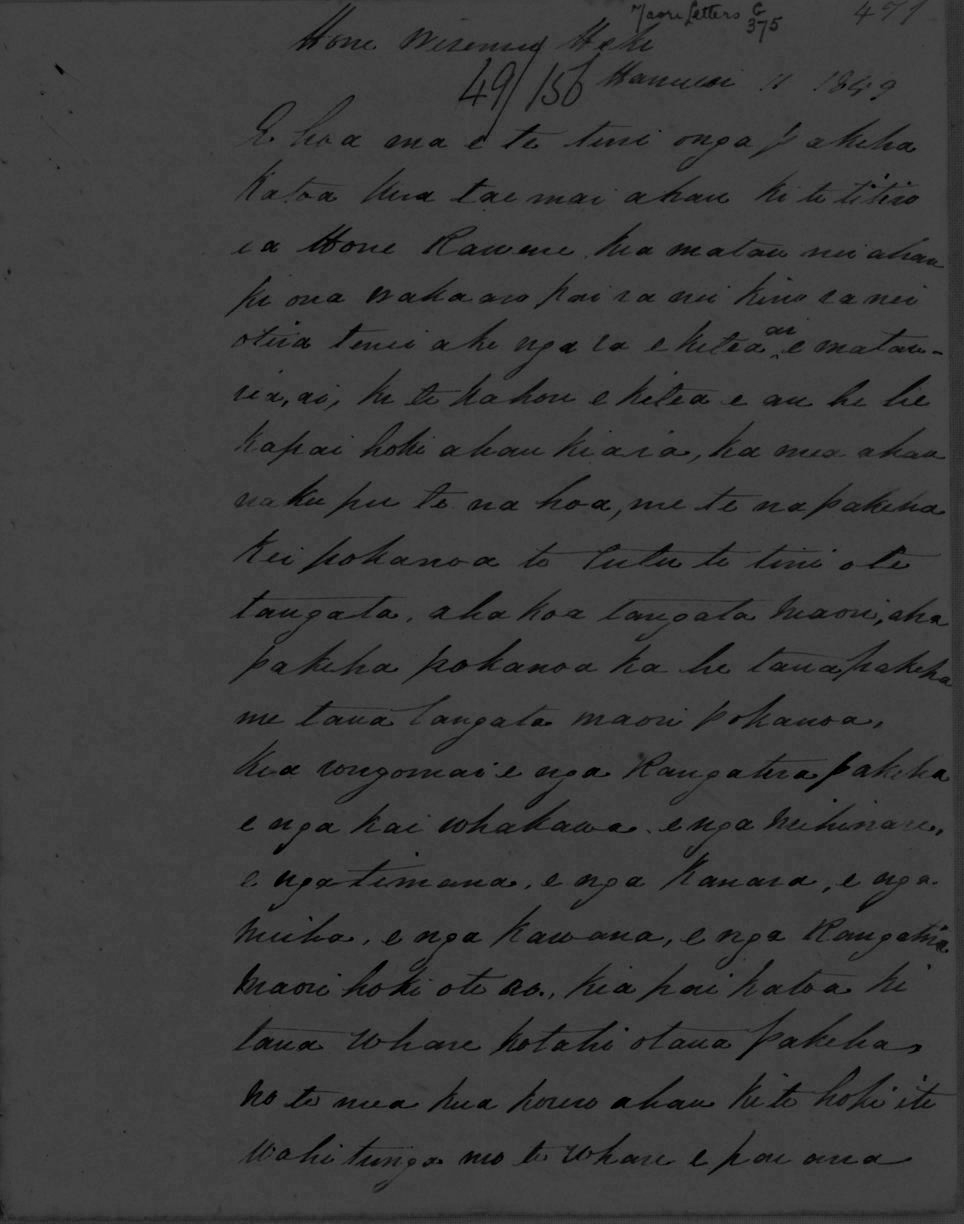

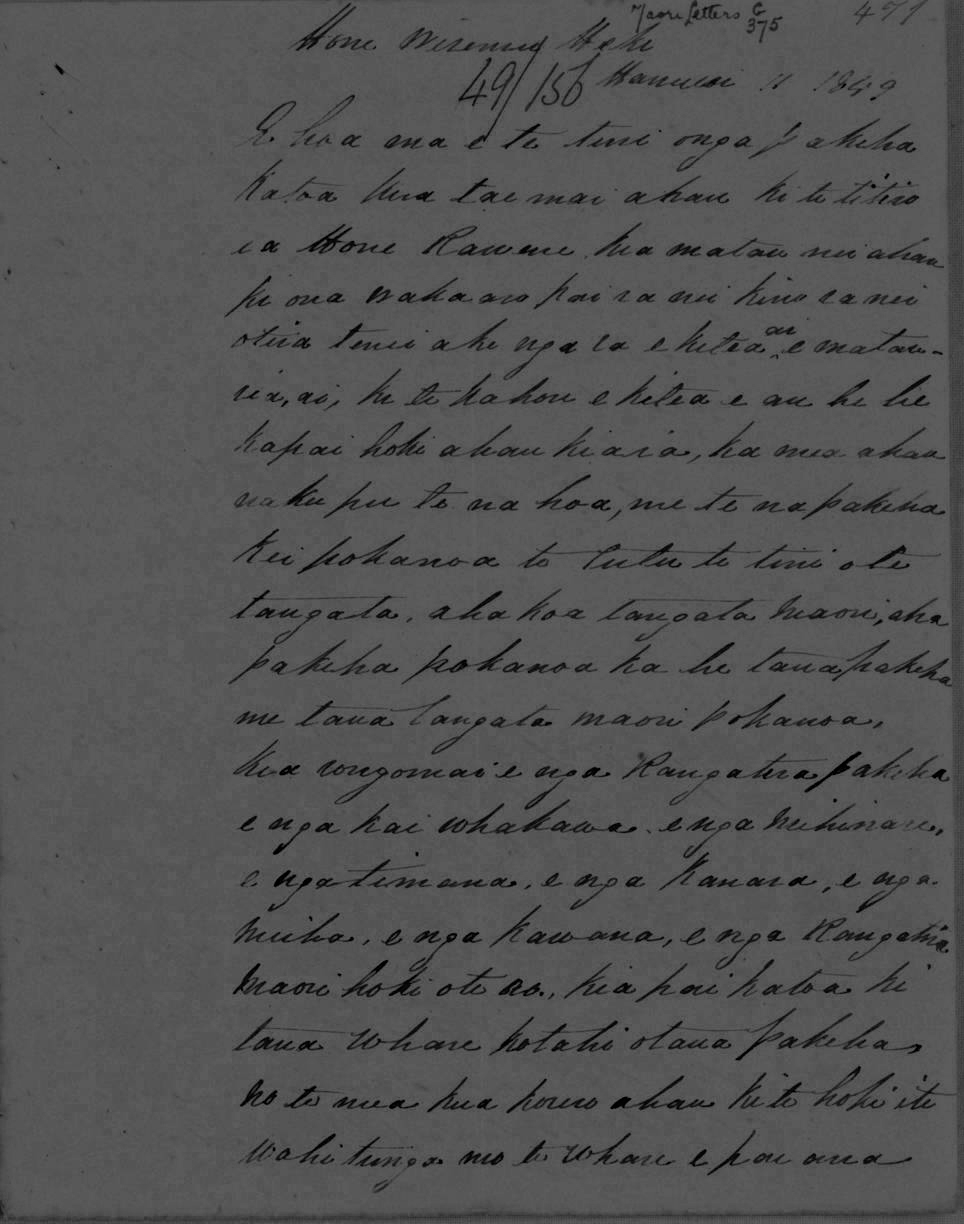

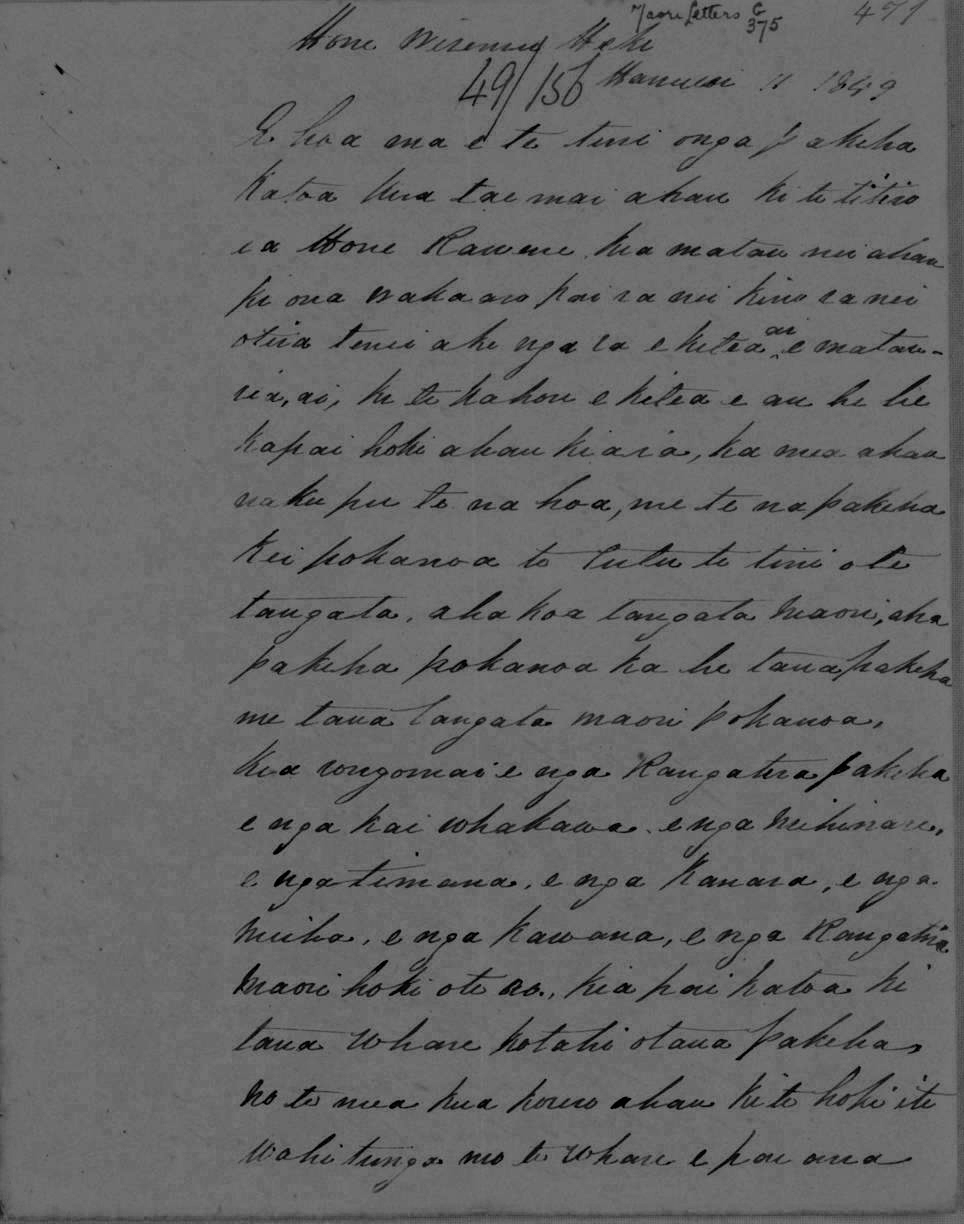

Letter to "all the many Pakeha", signed Hōne Wiremu Pokai Heke. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections GNZMA 375.

Letter to "all the many Pakeha", signed Hōne Wiremu Pokai Heke. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections GNZMA 375.

Recent studies have shown that while most of the letters were signed by Heke, it was Hariata who wrote them. The process was described by Hariata to artist Joseph Merrett not long after the war’s end:

“I myself wrote a letter from [Heke] to the Governor,” she explained. “I confined myself to civil language, and it was a good letter.”

Hōne Heke would live another four years after the war's inconclusive end. Hariata would go on to marry Arama Karaka Pī (Te Māhurehure). In 1868, a colonist caught sight of her in the Hokianga. She was at the head of an army of several hundred men:

"The lady was in her war garb with red jacket and red sash and red feathers... she was marching to the battlefield."

"If not heeded, then this peace with one another will end and I will become stubborn and free, a roaring lion to bite the tail of each star and there will be misfortune."

Letter from Hariata Rongo and Hōne Heke to Governor Grey, 1849

Today, the slates Rongo hid beneath the newly-constructed lean-to at Kemp House live at Kerikeri Mission Station. They are cared for by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga on behalf of Ngāpuhi and the Crown. In 2018 the slates were included in the UNESCO New Zealand Memory of the World Programme.

"Kei hea te pai? Kei hea te kupu whakatapu i tēnei motu? Kei hea te pupuri i te kupu a Heke?"

"Where is the goodness? Where is the sacred word of this island? How are the words of Heke being upheld?"

Letter from Hariata Rongo, c.1850