The Great White Fleet

Discover the time the United States of America made plans to invade Auckland.

By Paul Veart | Web and Digital Advisor

The Arrival

If you'd been standing on the summit of Maungauika on the morning of Sunday, 9 August 1908, you would have witnessed an astonishing sight.

It started as a wisp of smoke on the horizon, transforming into dark brown clouds. Then, suddenly, they appeared: 16 battleships, funnels belching, turrets bristling with guns as they made their way down the channel.

And each of them was painted a stark white.

These ships weren't your usual Auckland visitors. There was no sign of the Union Jack; no familiar faces. Instead, the Stars and Stripes flew from their bows. They had names like Kentucky and Connecticut and Alabama.

These arrivals were American. This was the Great White Fleet.

"Slumbering wickedness"

As the battleships entered the Waitematā Harbour, Auckland’s newspapermen got to work on their editorials – and they didn't hold back on the adjectives.

According to the Star, the fleet resembled “great white war dogs, athwart the blushing horizon of the early morn, nosing in slumbering wickedness”. The Herald was similarly excitable, declaring the fleet's arrival was "as great an event in our history as was the first visit of the intrepid voyager Captain Cook."

But what were 16 battleships and 14,000 sailors doing in the South Pacific, thousands of miles from home?

Origins

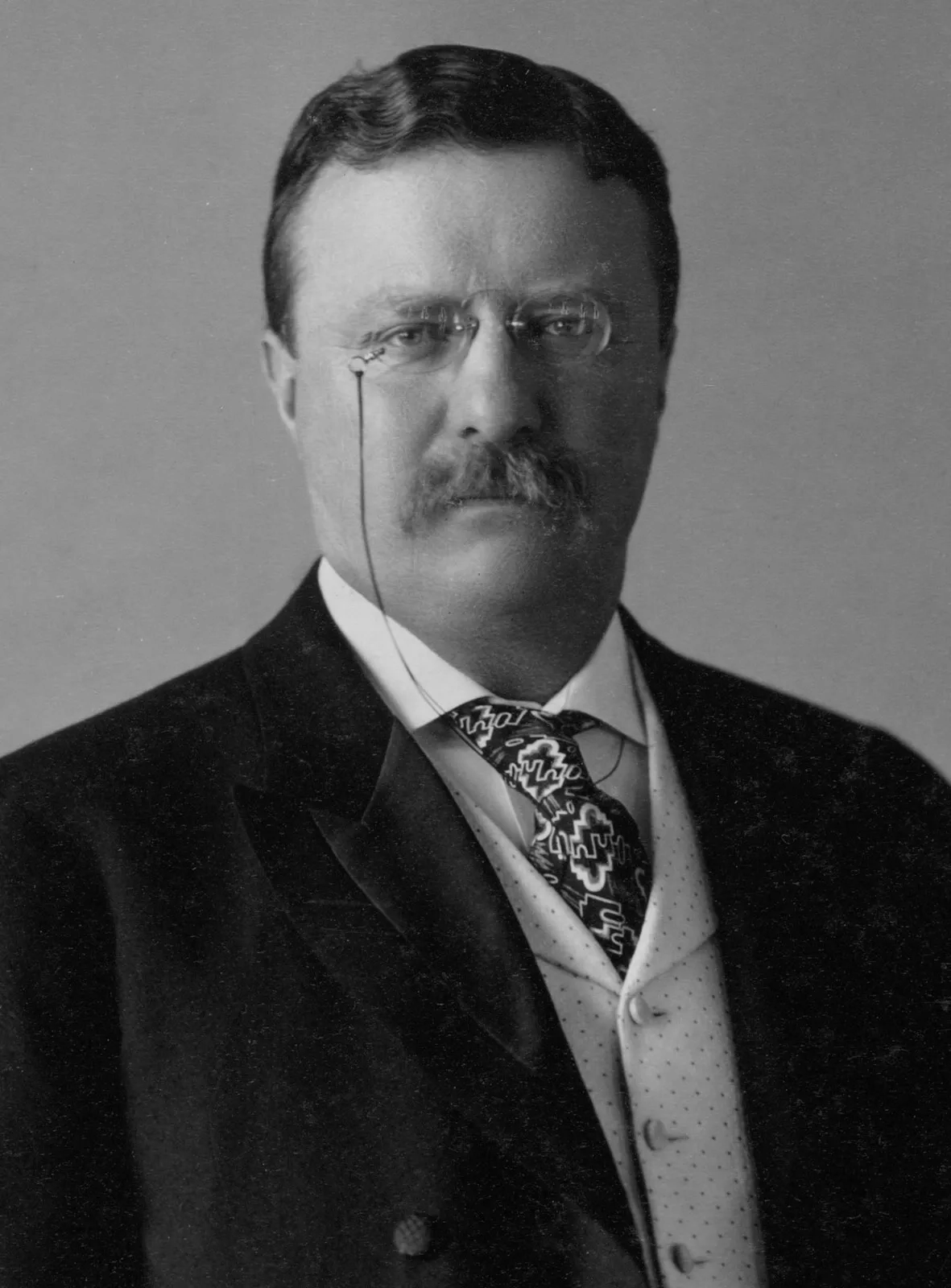

The Great White Fleet was the brainchild of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, part of a plan concocted in the aftermath of the Japanese defeat of the Russian Empire in 1905.

In New Zealand and Australia, the rise of a non-European power was seen by many as a worrying development. Both countries pursued overtly racist immigration policies, and the idea that Japan could become a dominant naval power created a feeling of "not a little suspicion and uneasiness".

Many Americans agreed. So, in December 1907, two squadrons of U.S. battleships set off on their round-the-world journey. The voyage had a number of aims, not least projecting military might, but it had other roles, too – including one that wouldn't become public for almost a century.

"WELCOME"

For most New Zealanders, the fleet's wider political motivations weren’t at the forefront of their minds on the morning of 9 August. Instead, they were preparing for something else:

A massive party.

On the day of the fleet's arrival, crowds began to gather near the harbour. They stood on beaches and maunga; they clustered on wharves; they lined streets and footpaths and rooftops.

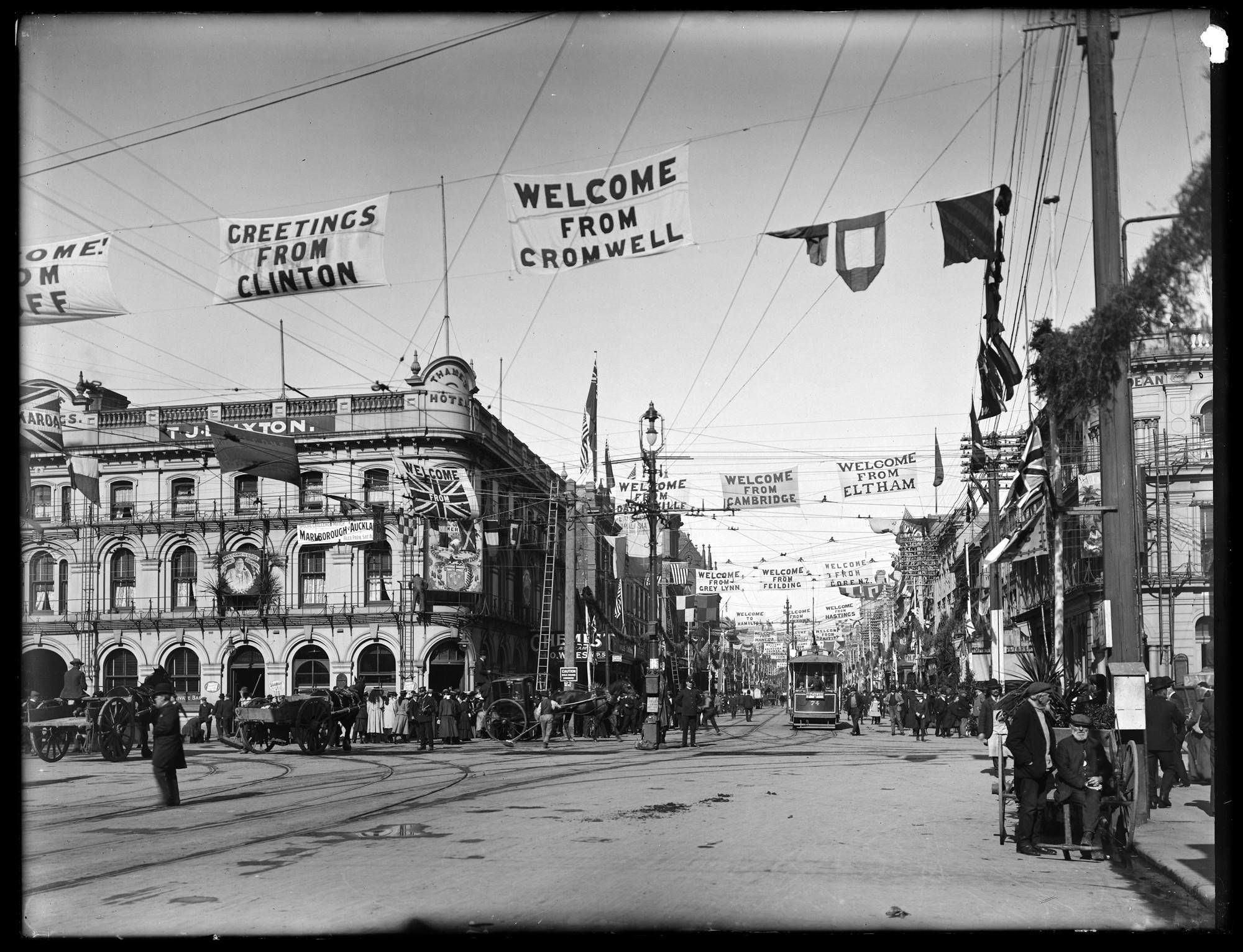

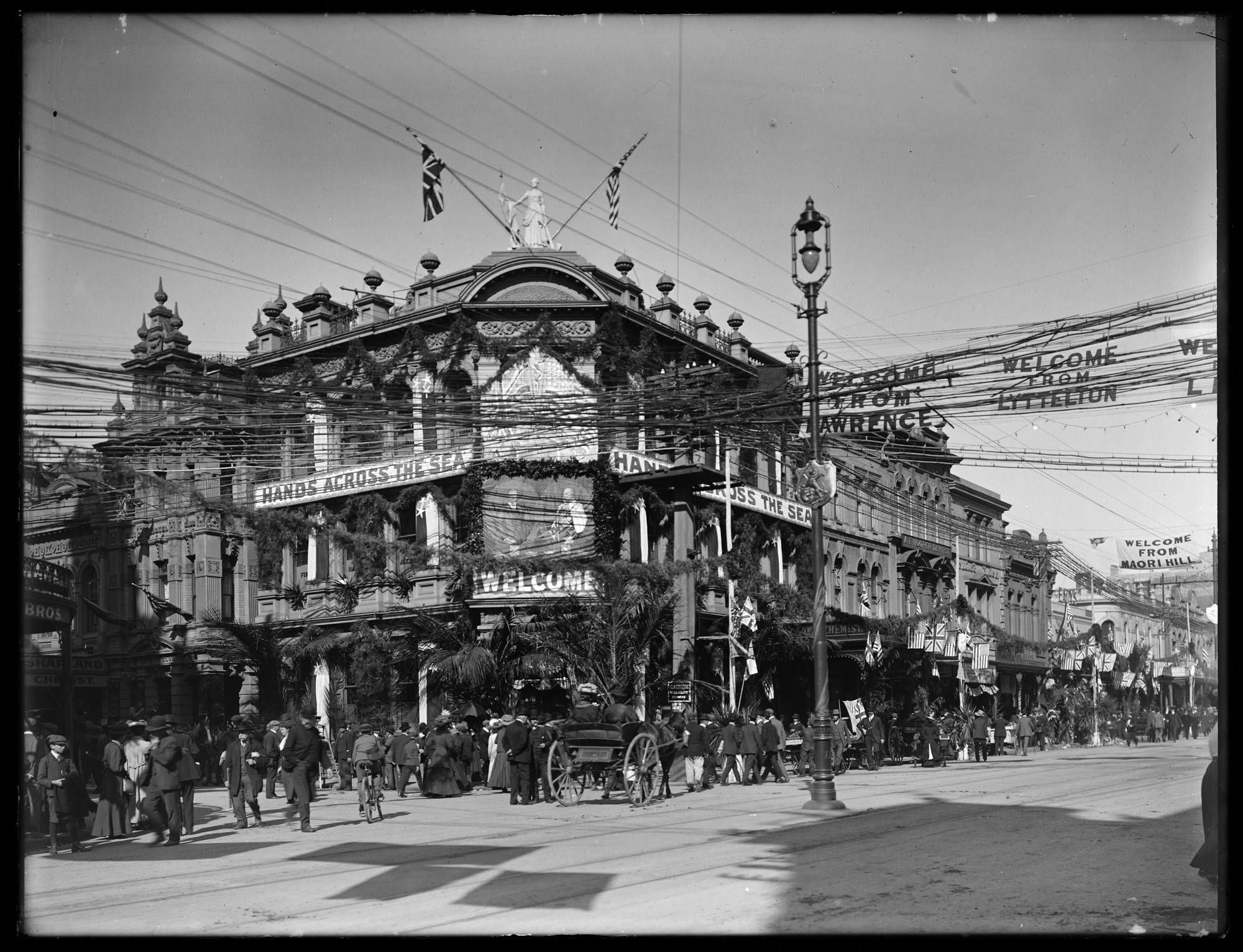

Banners were hoisted above Queen Street proclaiming greetings from across the country. Ceremonial arches were erected with electric lights spelling out "WELCOME". The Stars and Stripes fluttered from prominent buildings.

The politicians were there, too. Their trip to Auckland was a unique one, with MPs crowding the “Parliament Special” as it made its way north on the still unfinished main trunk railway line.

By the time Rear Admiral Charles Sperry and his officers made their way into the city, 100,000 New Zealanders had gathered to greet them – about 10% of the country's entire population.

Fleet Week

Over the next week, Auckland was transformed by its visitors. While the officers were whisked off to banquets and tree plantings, thousands of sailors enthusiastically explored the city's streets, suburbs and pubs.

Many Americans marveled at their encounters with locals. Journalist Franklin Matthews claimed, “if healthier, happier, more prosperous human beings than the residents of New Zealand exist anywhere in the world” he did not know where to find them.

Others – perhaps feeling homesick – compared New Zealand to Kansas and other states.

By the time the fleet set sail “after a week of unprecedented gaiety”, it was clear that the visit had been a political and financial success.

Except for one detail, unknown to New Zealanders at the time: the Americans had drawn up plans for an invasion...

Ngata's Response

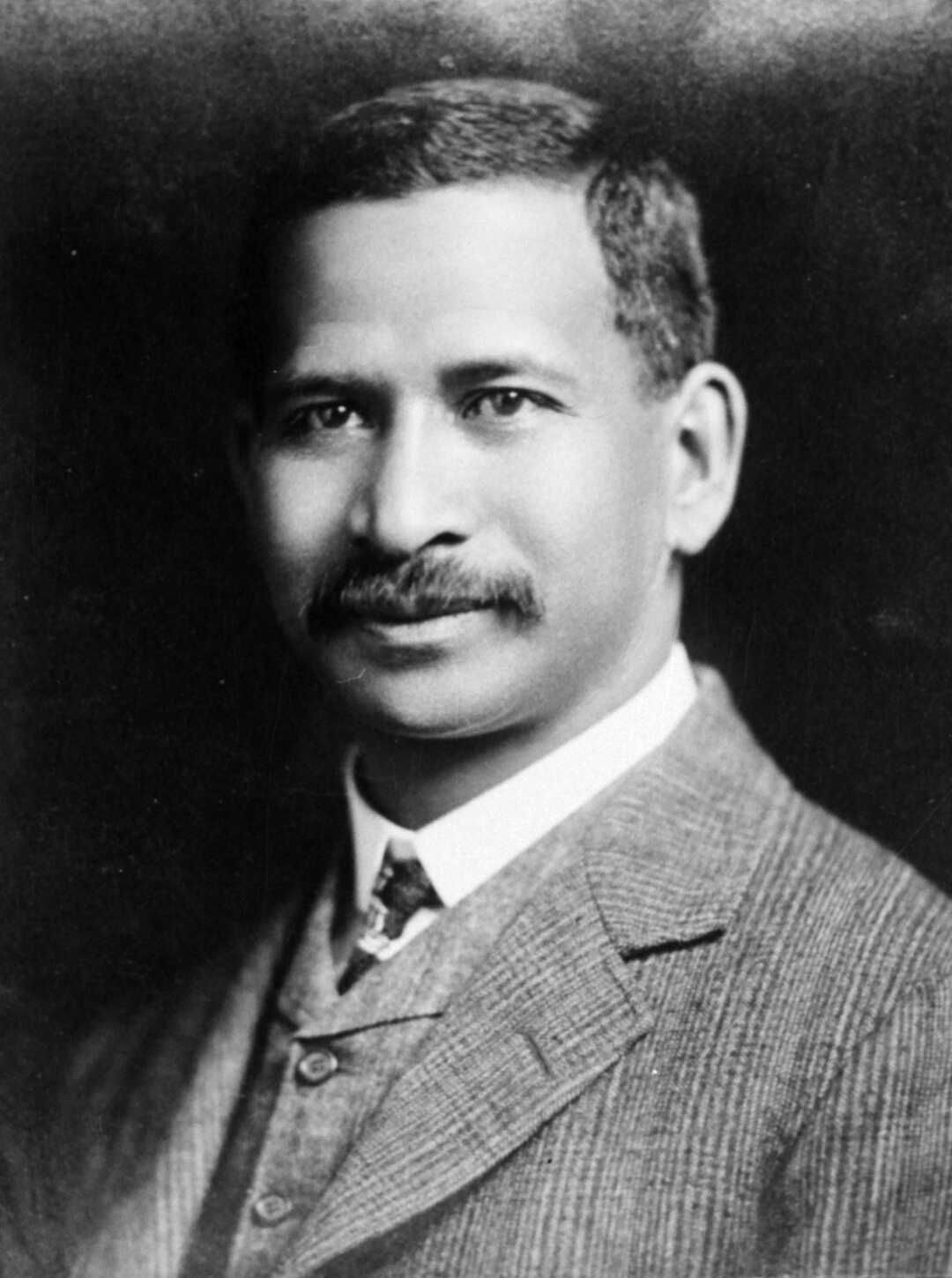

MP Āpirana Ngata was one of the few officials to highlight the ongoing racism faced by Black Americans, declining involvement in the welcome.

The Great White Fleet was a prime example of these racist policies. Since 1893, the United States Navy had systematically applied Jim Crow law to its enlisted personnel, including the segregation of spaces onboard ships and the removal of Black petty officers.

Over 70 Japanese-American sailors had also been transferred to other roles prior to the fleet's departure.

Mementos

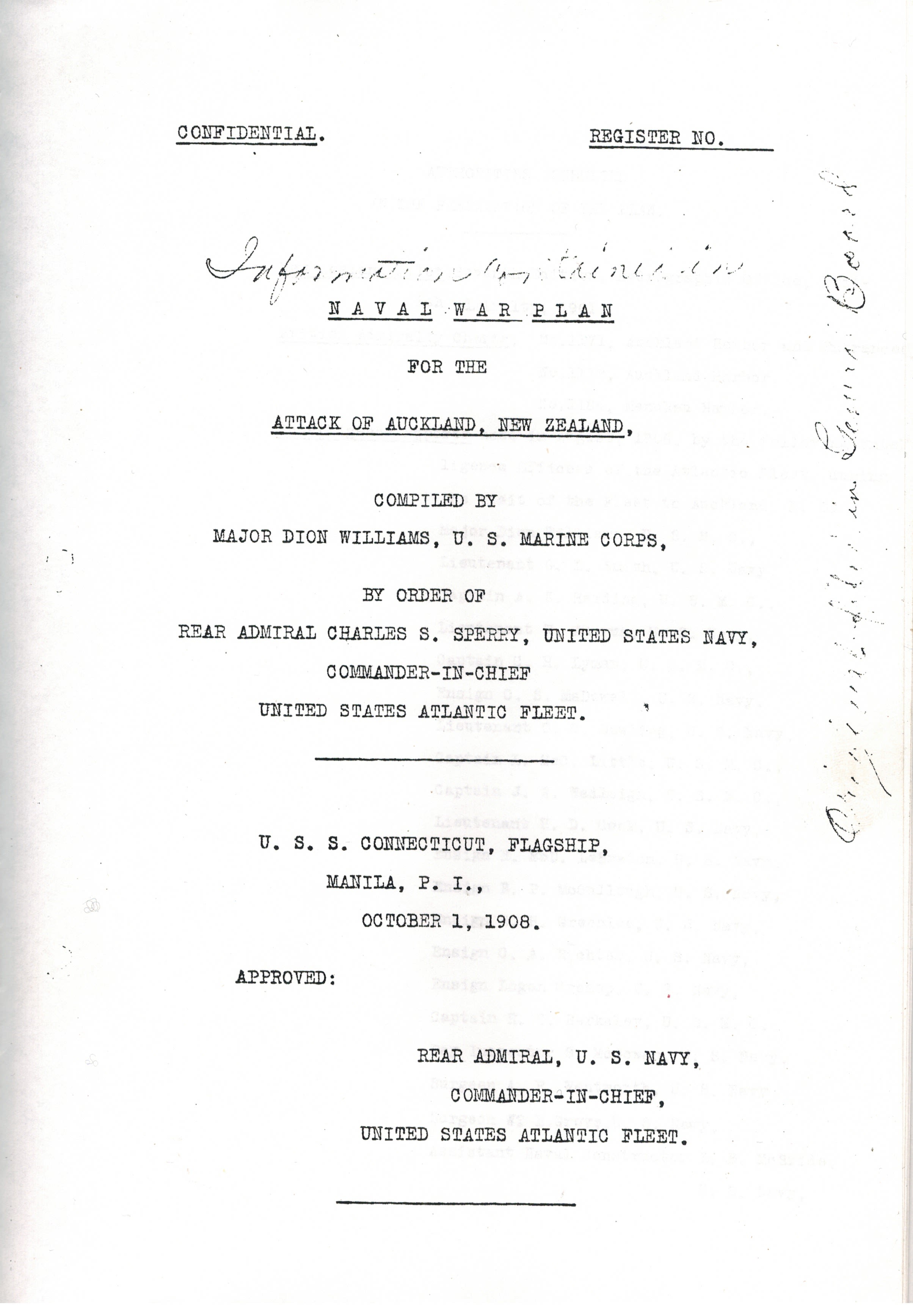

Everyone loves a souvenir. For many sailors in the Great White Fleet, this meant toys and snacks and especially the ever-popular postcards. But Rear Admiral Sperry organised a different memento for his time in New Zealand: a document entitled Naval War Plan for the Attack of Auckland, 1908.

The motivation for Sperry’s plan had come about not long after the fleet’s trip to Yokohama, which had convinced the rear admiral that war with Japan – and possibly Britain – was imminent.

He knew that for the Americans to gain supremacy in the Pacific, they would need to capture Sydney. And what better place to launch an attack on Sydney than Auckland?

So his staff got to work. During their week in Tāmaki Makaurau, they chatted with officers about mine fields; they photographed coastal defences; they studied the competency of local troops.

The report was so thorough, it even made note of picket fences, highlighting that they “might prove troublesome for cavalry”.

In the end, the Americans settled on two possible strategies: the first was to land guns on Rangitoto and shell Auckland’s coastal forts into submission, while the other was to attack through the Manukau Harbour.

After sign-off, Naval War Plan for the Attack of Auckland, 1908 – along with the equivalents for Sydney, Melbourne and Western Australia – were taken home and submitted to the Department of Navy. Sperry retired the following year, and (thankfully) his invasion plans remained untouched for the next nine decades.

Further Reading

You can find out more about the Great White Fleet via the U.S. Naval Institute and the Naval Historical Society of Australia. There is also extensive coverage in Papers Past.

For more on Jim Crow policies in the American navy, see Black Sailors, White Dominion in the New Navy, 1893 - 1942.

Images

The photographs in this story are courtesy of Auckland Libraries and are part of their Heritage Collections available via Kura: Heritage Collections Online.

Exceptions include the photo of President Theodore Roosevelt (available via the Library of Congress) and Sir Āpirana Ngata (available via the Alexander Turnbull Library).